Toivotamme teidät tervetulleeksi TaM Ismo Luukkosen väitöstilaisuuteen:

Valokuvan ajallisuus.

Maiseman kerrostumista ajan kokemukseen.

Perjantaina 3 marraskuuta 2017, klo 12.00–14.00

Iso Luentosali 822

8krs, Hämeentie 135 C

00560, Helsinki, FI

Väitöskirja on taiteellinen tutkimus, joka tuo esille tekijälähtöisen näkökulman ajan ja valokuvan suhteeseen. Väittelijä esittää tulkintoja ajasta, maiseman kerrostumista sekä muinaisjäännöksistä maisemassa, ja tuo samalla kuvan sekä kuvan tekemisen kiinteäksi osaksi tutkimusta.

Vastaväittäjä: KuT Jan Kaila, Taideylipiston kuvataideakatemia

Kustos: prof. Merja Salo, Aalto-yliopiston Median laitos

Keskustelu käydään suomeksi.

ABSTRAKTI

Valokuvan ajallisuus (Maiseman kerrostumista ajan kokemukseen) on tekijälähtöinen taiteellinen tutkimus valokuvan ja ajan suhteesta. Muinaisjäännökset maisemassa, maiseman ajallinen kerroksellisuus ja sen välittyminen maisemavalokuvissa ovat työni lähtökohtia, joiden johdattamana tarkastelen valokuvan ajallisuutta. Pyrin vastaamaan kysymykseen, kuinka aika esiintyy valokuvissa.

Tutkimuksen rakenne on dialoginen. Tutkimustekstin rinnalla on kuvallisia lukuja, jotka pohjautuvat vuosien 2000–2017 taiteelliseen työskentelyyni maisemassa olevien muinaisjäännösten ja valokuvan ajallisuuden parissa. Kuvaustyössäni olen pyrkinyt tarkastelemaan kohteitani erilaisista lähtökohdista, mikä näkyy myös kuvien ilmiasuissa. Kuvallinen työskentelyni on tapahtunut samanaikaisesti teoreettisen tutkimuksen kanssa ja työskentelytavat ovat vaikuttaneet toisiinsa. Kuvalliset luvut tuovat toisen tarkastelutavan sanallisten rinnalle. Ajattelutapa on toinen, mutta tarkastelun kohde yhteinen.

Valokuvan voi nähdä todellisuuden jälkenä tai kuvallisena tulkintana todellisuudesta. Nämä kaksi näkökulmaa esiintyvät rinnakkain sekä tutkimustekstissä että kuvallisissa luvuissa. Kun katson valokuvaa todellisuuden jälkenä, sen ajallisuus liittyy kohteen ajallisuuteen, esimerkiksi maiseman ajallisiin kerrostumiin ja niiden välittymiseen valokuvasta. Jotta ajallisuuden voi tunnistaa kuvasta, se on ymmärrettävä myös kohteena olevasta maisemasta. Mutta jälki sitoo valokuvan aikaan myös toisella tavalla. Kuvattu hetki on tietty ajankohta menneisyydessä, joka väistämättä karkaa kauemmaksi ajan jatkumolla. Mennyt hetki tulee näkyväksi esimerkiksi vertailun kautta. Kuvaa voi verrata toisiin kuviin (samasta kohteesta) tai itse kohteeseen.

Katsoessani valokuvaa todellisuuden kuvallisena tulkintana, sen ajalliset merkitykset ovat riippuvaisia myös valokuvaajan tekemistä valinnoista. Valokuvaajana voin vaikuttaa siihen, kuinka aika jättää merkkinsä kuvan pintaan. Ajallisuutta voi edelleen korostaa käyttämällä erityisiä tekniikoita, joissa aika jo kuvattaessa muovaa valokuvan ilmiasua. Esimerkiksi pitkällä valotusajalla kuvattaessa esiintyvä liike-epäterävyys voi johdattaa katsojan ajallisten merkitysten äärelle.

Valokuva on kuitenkin monitulkintainen, sitä voi tarkastella monista näkökulmista ja erilaisista lähtökohdista. Tulkinta ei aina pysy niissä raameissa, joita tekijä yrittää kuvalle asettaa. Valokuvan merkitykset riippuvat siitä, kuinka katsoja kuvan kohtaa. Tähän kohtaamiseen vaikuttaa valokuvan ilmiasun ja katsojan itsensä lisäksi myös esityskonteksti, se, millaisessa yhteydessä kuva esitetään ja mitä muita kuvia tai tekstejä kuviin liittyy. Näin voidaan johdatella katsojaa myös ajallisiin tulkintoihin.Valokuvalla on myös oma ajallisuutensa. Se on esine, joka vanhenee minkä tahansa esineen lailla, mutta vielä olennaisemmin ajallisuus tuntuu välimatkassa, joka syntyy valokuvan ottamisen ja katsomisen hetkien väliin. Valokuvaa katsotaan aina jälkikäteen. Se on väistämättä sidoksissa menneeseen ja tietoisuus tästä vaikuttaa siihen, kuinka kuvaa katsotaan. Valokuva on jäännös hetkellisestä tapahtumasta.

Tervetuloa!

You are cordially invited to the Defence of Doctoral Dissertation of MA Ismo Luukkonen:

Temporality of a photograph.

From the layers of a landscape to the experience of time.

Friday 3 November 2017, 12.00–14.00

Lecture Hall 822

8th floor, Hämeentie 135 C

00560, Helsinki, FI

The dissertation is artistic research into the relationship between a photograph and time. Photographing of prehistoric objects in landscape are used to examine the temporality of photography.

Opponent: Doctor of Fine Arts Jan Kaila, University of the Arts Helsinki

Custos: prof. Merja Salo, Aalto University Department of Media

Discussion will be held in Finnish.

ABSTRACT

The temporality of a photograph (from the layers of a landscape to the experience of time) is artistic research into the relationship between a photograph and time. The prehistoric objects in a landscape, the temporal layers of the landscape and the way the temporality of the landscape is represented in photographs are the starting points of the research. They led me to the key issue: the temporality of a photograph. My question is how time appears in photographs.

The structure of the research is dialogic. There are pictorial chapters beside written ones. The photographs are the results of my artistic work in the years 2000–2017, concerning prehistoric remains in the landscape and the temporality of a photograph. In my photographic work, my aim has been to examine subjects using different approaches. This is also visible in the appearances of the images. My photographic work has been concurrent with the theoretical research, and the two ways of working have affected each other. The way of thinking is different, but the subject is shared.

A photograph can be seen as a trace of reality or as a pictorial interpretation of reality. These two approaches appear both in the written text and in the pictorial chapters. When a photograph is thought of as a trace of reality, its temporality is based on the temporality of the subject, such as the temporal layers of a landscape and their representation in a photograph. To be able to recognise the temporality in the photograph, one must understand the temporality of the subject. However, the photograph as a trace also ties the photograph to time in another way. The photographed moment is a point in time, in the receding past. The gone moment of the photograph becomes visible, for example, if the photograph is compared to another photograph (of the same subject) or to the subject itself.

When I look at a photograph as a pictorial interpretation of reality, the temporal meanings also depend on the choices the photographer makes. As a photographer, I can decide how time leaves its mark on the surface of the photograph. The temporality can be emphasised by special techniques. A long exposure, for example, has an effect on the visuality of the photograph, and it can lead the viewer to temporal interpretations.

The photograph is, however, ambiguous. It can be studied from different viewpoints and using different approaches. The interpretation does not always stay within the frame that the photographer has suggested. The meanings depend on the way the viewer confronts the photograph. They are affected by the appearance of the photograph and the personality of the viewer, but also by the context of the photograph: where it is shown and what other pictures or texts are present. The context can be used to suggest temporal interpretations.

The photograph also has a temporality of its own. It is an object that ages like any object does, but even more essentially, temporality is felt in the distance between the moment when the photograph was taken and the moment when it is viewed. A photograph is always seen afterwards. It is inevitably bound to the past, and the awareness of this affects the way the photograph is viewed. A photograph is a remnant of a momentary incident.

WELCOME!

Jane Vita – Brazilian living in Finland – Service Design Lead at Digitalist and Ph.D. student at Aalto, New media, LeGroup.

Jane Vita – Brazilian living in Finland – Service Design Lead at Digitalist and Ph.D. student at Aalto, New media, LeGroup.

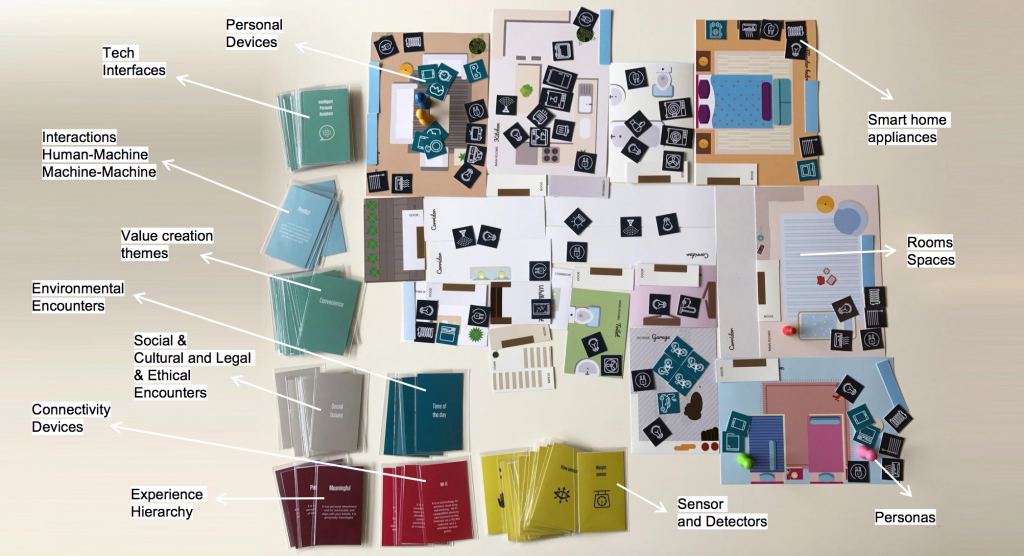

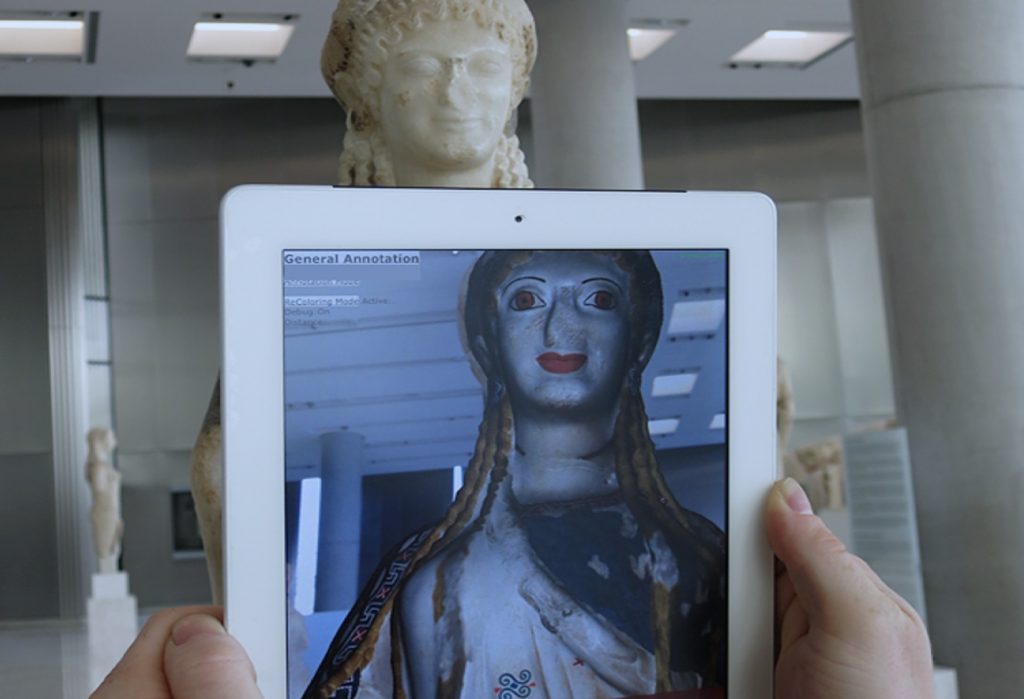

Jihye Lee is a visiting researcher at the Department of Media at Aalto University, and a recent PhD graduate in Film and Digital Media Design at the Hong Ik University, Seoul, South Korea. Her PhD thesis was about participatory process in mobile Augmented Reality with anthropological approach. She has worked in cultural institutions and colleges with interest in interactive storytelling and participatory design. Due to recent participation in digital heritage museum project in Korea, she has begun to focus on designing in digital heritage sector.

Jihye Lee is a visiting researcher at the Department of Media at Aalto University, and a recent PhD graduate in Film and Digital Media Design at the Hong Ik University, Seoul, South Korea. Her PhD thesis was about participatory process in mobile Augmented Reality with anthropological approach. She has worked in cultural institutions and colleges with interest in interactive storytelling and participatory design. Due to recent participation in digital heritage museum project in Korea, she has begun to focus on designing in digital heritage sector.