Archaeology of Media Infrastructures Winter-Spring 2019 DOM-E5006

Wednesdays 15.15 – 17.00

Dr. Samir Bhowmik

samir.bhowmik@aalto.fi

Media Lab / Department of Media

Aalto University School of Arts Design and Architecture

Course Summary

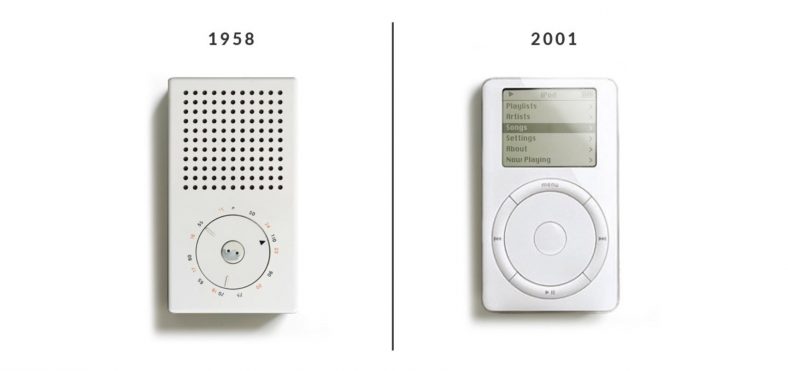

The course provides a framework of archaeological exploration of media infrastructures. It allows students to think beyond a single media device and design for broader media ecologies. Tracing the emergence of contemporary media infrastructures from early instances in human and media history, it examines both hard infrastructure (architecture, mechanical and computing systems) and soft infrastructure (software, APIs and operating systems). What are the breaks, the discontinuities and ruptures in media-infrastructural history? What has been remediated, in what form, in what characteristics? The course prepares students for the follow-up course: ‘Media and the Environment’ in Autumn 2019.

Study Material: Recommended reading list. Readings as PDFs will be posted in the study materials folder in myCourses.aalto.fi

Assessment Methods and Criteria: Classes are spread over Winter-Spring 2019. 80% attendance and completed assignments are required to pass the course. Co-authored short paper based on selected themes as final assignment, and/or prototypes that demonstrate aspects of the subject.

Grading Weightage:

In-class Discussion: 30% / Documentation (blog): 40% / Final Project / Article: 30%

*Students who stay above 50% will Pass.

Documentation

– Course blog: https://blogs.aalto.fi/mediainfrastructures/ Login will be provided.

– Every student will contribute to the blog. You are expected to post every week before start of class a 1 page text (300 words).

– Read the assigned literature for each class. These can be found from the Syllabus, and as well from myCourses.aalto.fi.

– Annotate and write a 1 page text. This document may have images / video / links etc.

– The text can be your reflections, examples, projects, ideas etc. as related to the topic and literature of the week. This may also contain the building blocks of your own final project / article whether it may be a piece of writing, visualization or project.

– Final projects must also be posted on the course blog.

– Besides the required documentation, you are free to post anything else related to the subject, that could be useful to you or others.

– Documentation to the blog will hold a 40% weightage for a pass/fail grade. At least 5 posts out of max total of 8.

Schedule of Classes

Week 1 – February 27: Course Overview

We will discuss the various aspects of the course including themes, topics, analyses and documentation. Also, we will talk about choosing individual or group projects for the course.

Summary of Case Studies:

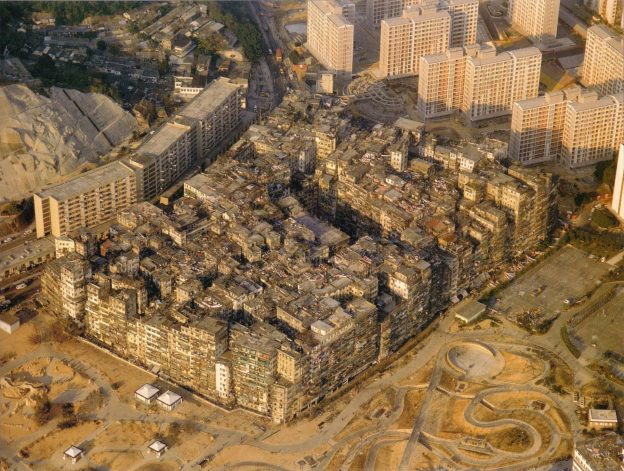

– Urban Media Infrastructures

– Memory Infrastructures

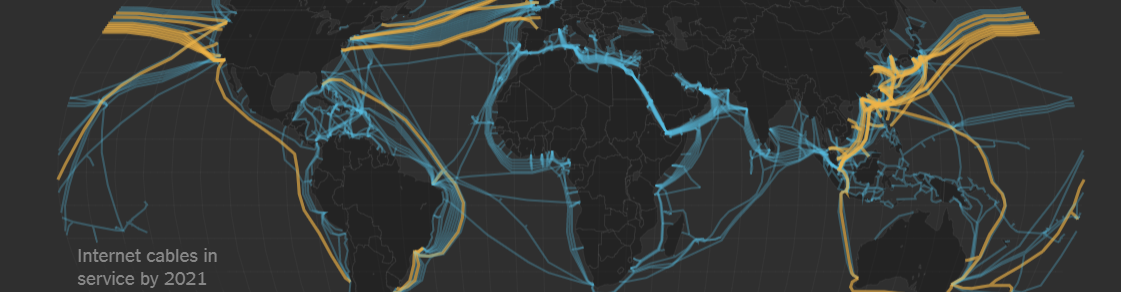

– Global Communications Infrastructures

– Artificial Intelligence (AI) Infrastructures

Week 2 – March 6: Media Infrastructure: Introduction

LECTURE

DISCUSSION IN-CLASS:

Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski, “Introduction,” in Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures, ed. Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski (Urbana, Chicago And Springfield: University Of Illinois Press, 2015), 1-27.

DEBATE (2-3 teams): Medium (single device) vs Infrastructural Approaches

Secondary Readings:

-

- Susan Leigh Star, The Ethnography of Infrastructure, American Behavioral Scientist 43 (3), 1999: 377-391.

- Brian Larkin, “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure,” Annual Review of Anthropology 42 (2013): 327-343.

Week 3 – March 13: Deep Time of Media / Infrastructure

LECTURE

DISCUSSION IN-CLASS:

Shannon Mattern, “Deep Time of Media Infrastructure,” in Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures, ed. Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski (Urbana, Chicago And Springfield: University Of Illinois Press, 2015): 95-102.

DEBATE (2-3 teams): Methods for Digging into Infrastructure

Secondary Reading:

-

- Benjamin Bratton, The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty, MIT Press, 2015.

- Friedrich Kittler, The History of Communication Media, in C-Theory, 1996: https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/ctheory/article/view/14325/5101

- Siegfried Zielinski, “Introduction: The Idea of a Deep Time of Media,” in Deep Time Of The Media: Toward An Archaeology Of Hearing And Seeing By Technical Means (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006): 1-11.

- Shannon Mattern, Introduction: Ether/Ore, Code and Clay, Data and Dirt: Five Thousand Years of Urban Media (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017).

- Jean-François Blanchette, “A Material History of Bits,” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 62, no. 6 (June 2011): 1042–1057.

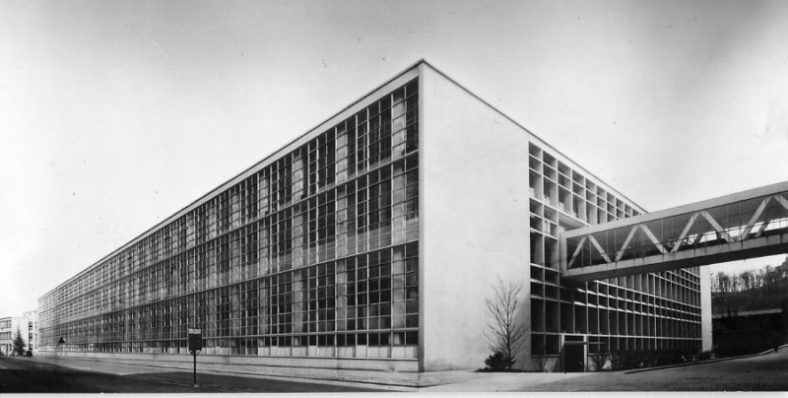

Week 4 – March 20: Digital Media and Cloud Infrastructure

LECTURE

DISCUSSION IN-CLASS:

Jennifer Holt and Patrick Vonderau, “Where the Internet Lives”: Data Centers as Cloud Infrastructure,” in Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures, ed. Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski (Urbana, Chicago And Springfield: University Of Illinois Press, 2015), 71-93.

– Steven Levy, Where Servers Meet Saunas, WIRED, 2012: https://www.wired.com/2012/10/google-finland-data-center-2/

DEBATE (2-3 teams): Why the Infrastructure of the Internet remains invisible and how can this be remedied?

Secondary Reading:

-

- Sean Cubitt, Robert Hassan and Ingrid Volkmer, “Does Cloud Computing Have a Silver Lining?” Media Culture Society 33 (2011): 149-158

- Jason Farman, “Invisible and Instantaneous: Geographies of Media Infrastructure from Pneumatic Tubes to Fiber Optics,” Media Theory, May 18, 2018.

- Paul Dourish, Protocols, Packets, and Proximity: The Materiality of Internet Routing, in Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures, ed. Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski (Urbana, Chicago And Springfield: University Of Illinois Press, 2015), 183-204.

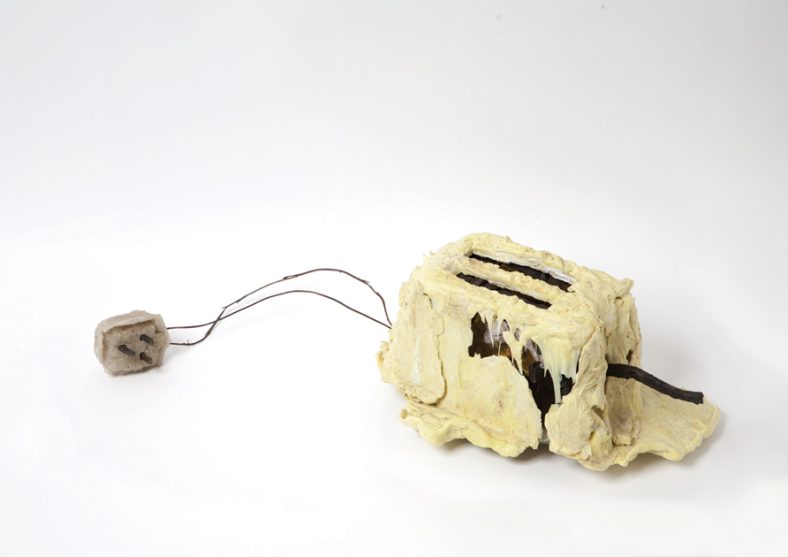

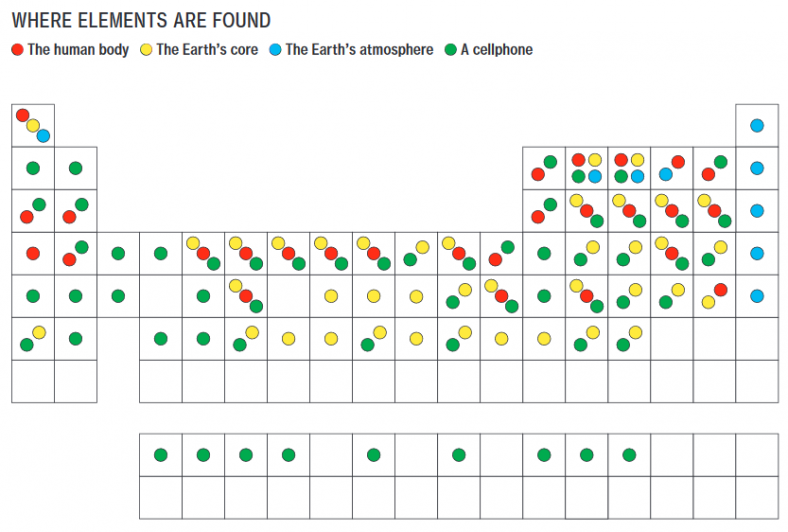

Week 5 – March 27: Materialities of Media Infrastructures

LECTURE

DISCUSSION IN-CLASS:

Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler, Anatomy of an AI System (2018), https://anatomyof.ai

DEBATE (2-3 teams): What is the Future of AI Infrastructure / AI assistants

Secondary Reading:

Week 6 – April 3: Labor, Repair, Maintenance of Media Infrastructures

**Presentations of Student Project proposals**

LECTURE

DISCUSSION IN-CLASS:

Jussi Parikka, Dust and Exhaustion: The Labor of Media Materialism, C-Theory, 2013: http://ctheory.net/ctheory_wp/dust-and-exhaustion-the-labor-of-media-materialism/

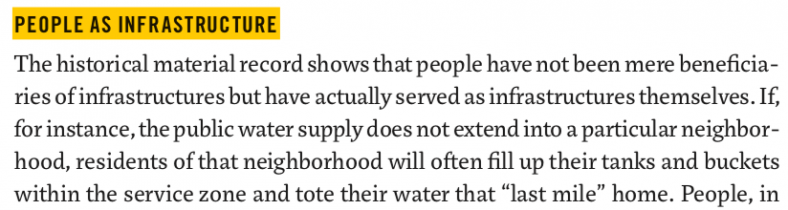

DEBATE (2-3 teams): People / Labor as Media Infrastructure

Secondary Reading:

—————Break————-NO CLASS on April 10———-Break———————

Week 7 – April 17: Infrastructural Inequality, Differences and Disruption

**Presentations of Student Project/Article proposals**

LECTURE

DISCUSSION IN-CLASS:

Lisa Parks, Water, Energy, Access: Materializing the Internet in Rural Zambia, in Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures, ed. Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski (Urbana, Chicago And Springfield: University Of Illinois Press, 2015), 115-136.

DEBATE (2-3 teams): Approaches to global media inequality.

Secondary Reading:

-

- Mark Warschauer, Economy, Society, and Technology: Analyzing the Shifting Terrains, in Technology and Social Inclusion: Rethinking the Digital Divide (MIT Press, 2003), 11-30.

- Pippa Norris, Digital Divide: Civic engagement, information poverty, and the Internet worldwide (Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Week 8 – April 24: Approaches to Media Infrastructure

**Presentations of Student Project/Article proposals**

***Sign-up for Spring Demo Day 2019***

LECTURE

DISCUSSION IN-CLASS:

Jamie Allen, Critical Infrastructure, APRJA 2014: http://www.aprja.net/critical-infrastructure/

DEBATE (2-3 teams): What approaches to study Media Infrastructure?

Secondary Reading:

-

- Matthew Kirschenbaum, Introduction: Awareness of the Mechanism, Mechanisms: New Media and the Forensic Imagination (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008): Jussi Parikka, Geology of Media (University of Minnesota Press, 2015): 1-24.

- Wolfgang Ernst, Media Archaeography: Method and Machine versus History and Narrative of Media, in Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications and Implications (University of California Press, 2011): 239-255.

- Shannon Mattern, Deep Mapping the Media City (University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

- Jussi Parikka, “Operative Media Archaeology: Wolfgang Ernst’s Materialist Media Diagrammatics,” Theory, Culture & Society 28 (2011): 52–74

Week 9 – May 8: Final Student Project/Article Presentations

Final Article submissions: May 15. (To be posted on the Course blog)

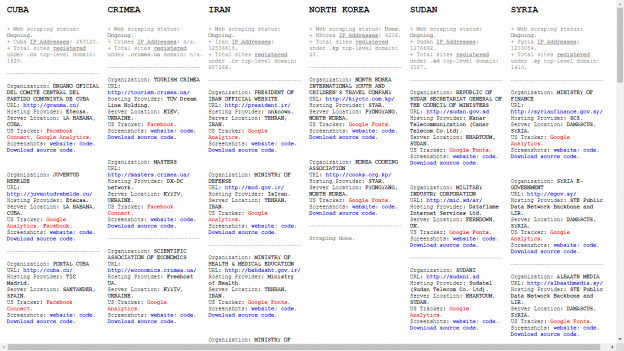

source: https://carbonfeed.org

source: https://carbonfeed.org