Performance art scene can date back to the primitive people in Paleolithic era creating sacred rituals to emulate the spirit world. It is quite burdensome to produce the exact date of birth of the performance art, as in its essence it is a pure transmission of energy between the artist and the audience at certain given time and space; it happens in present – once the piece is over, it is over forever, only the memory of it can stay. This changes, however, with the birth of media technology, in particular the first film camera.

Kodak created first film camera in the late 80s [1], the first transparent and flexible film base material was nitrocelluloid [2], which was discovered and then refined for the use in film. Now, with this first film camera the performances were possible to capture, store and document them for later use. The performance trace was no longer only in viewer’s memory, but also on a piece of paper.

(Photo 1: Original Kodak Camera, Serial No. 540, [3])

Nitrate film was used for both photographic and cinematic images from late 19th century until late 40s in 20th century [2]. During this time in performance history, quite a popular style was cabaret. With the birth of revolutionary cultural movements like DADA and Cubism, performance art started to shape its importance in the bourgeoisie fine art society. Performance art was considered and still is, nowadays, as one of the purest artistic expressions. Quite challenging to capture the time and space of a certain moment on film, yet quite revolutionary, provocative and important for the history and theory of performance art the photographs were in the beginning of 20th century.

(Photo 2: Cabaret Voltaire, [4])

However, photographs do not depict the movements, the feelings and expressions of the performer. They are just a still candid photograph of a certain time and moment in that given space. During the same era a new art form in media was born – motion pictures and the first synthetic plastic was produced and patented by Leo Baekeland in 1907 [2]. Polymers like cellulose nitrate, cellulose acetate and polyester play an important role in film history as well as in the making and documenting of the performance history. Many film rolls were used and discarded in the landfill, where most traditional plastics might not decompose.

With the creation of digital cameras in 70s and 80s the feeling of many wasteful materials discarded, like film rolls, seems to have disappeared. But is it really quite so? Inside the digital camera, there are many electronic equipments, sensors, detectors that capture the incoming rays and turn them into digital signals. Digital cameras use digital technology. “Plastics are often neglected within materialist accounts of media” as rightfully Sy Taffel said in their paper “Technofossils of the Anthropocene: Media, Geology, and Plastics. Cultural Politics” [2]. If we go beyond digital camera as a medium to document performance art, we can think of the quite recent concept of the art of the future, for example mixed reality. Mixed reality can truly help the artist to caption their performance forever. The feeling and experience for the viewer is quite different and incomparable to viewing the performance piece, for example, in the form of photograph or a movie. In mixed reality the viewer can be present with the performer in space. It is no longer the documented trace of performance you are viewing, it is almost like a feeling that you are there together with an artist.

Performance art is art quite often without objects that happen in given space and moment. In order to be present, the viewer needs to be physical in that space. But with the help of the media the viewer can experience partially or fully the artwork. Their symbiosis is strong and it plays an enormous role in the history, theory and development of performance as an art form. The symbiosis of media and plastics might not be as visible to the naked eye, however, it is daily there in our everyday lives capturing incoming rays, detecting the change in the environment and responding with the output. We cannot talk about one without the other, thus performance, media and plastics are tied together in the technosymbiosis of anthropocene.

As a final thought, here is a small performance and entertainment to compare thermoplastics and thermoset plastics.

(Video 1: Comparison of plastics in digital media 1, thermoplastics examples, by the author)

(Video 2: Comparison of plastics in digital media 2, thermoset plastics examples, by the author)

References:

[1] Ma, Jonathan. (2017). Film Photography History and Emergence of Digital Cameras. https://sleeklens.com/the-history-of-film-and-emergence-of-digital-cameras/ [Accessed 4 October 2020]

[2] Taffel, Sy. (2016). Technofossils of the Anthropocene: Media, Geology, and Plastics. Cultural Politics. 12. 355-375. 10.1215/17432197-3648906

[3] National Museum of American History. Original Kodak Camera, Serial No. 540. https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_760118 [Accessed 5 October 2020]

[4] Sooke, Alastair. (2016). Cabaret Voltaire: A Night out at History’s Wildest Nightclub. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20160719-cabaret-voltaire-a-night-out-at-historys-wildest-nightclub [Accessed 5 October 2020]

Infragraphy is a compilation of critical student artworks and short essays dealing with the materialities of media technologies and their environmental implications. The volume presents artworks and texts from the course ‘Media and the Environment’ in the Fall of 2020 at the Department of Media, Aalto University. The course is a series of scholarly readings about and around the themes of media including media’s relations and impacts on the so-called Anthropocene, thermocultures of media, ecologies of fabrication, media and plastics, Internet of Things, Planned Obsolescence, e-waste, and media’s energetic landscapes. A key approach of the course is to introduce artistic methods and practices that could address emerging media materialities. The student artistic outputs are presented in a final exhibition.

Infragraphy is a compilation of critical student artworks and short essays dealing with the materialities of media technologies and their environmental implications. The volume presents artworks and texts from the course ‘Media and the Environment’ in the Fall of 2020 at the Department of Media, Aalto University. The course is a series of scholarly readings about and around the themes of media including media’s relations and impacts on the so-called Anthropocene, thermocultures of media, ecologies of fabrication, media and plastics, Internet of Things, Planned Obsolescence, e-waste, and media’s energetic landscapes. A key approach of the course is to introduce artistic methods and practices that could address emerging media materialities. The student artistic outputs are presented in a final exhibition.

INFRAGRAPHY Volume 2. is a compilation of critical student artworks and short essays dealing with the materialities of media technologies and their environmental implications.

INFRAGRAPHY Volume 2. is a compilation of critical student artworks and short essays dealing with the materialities of media technologies and their environmental implications.

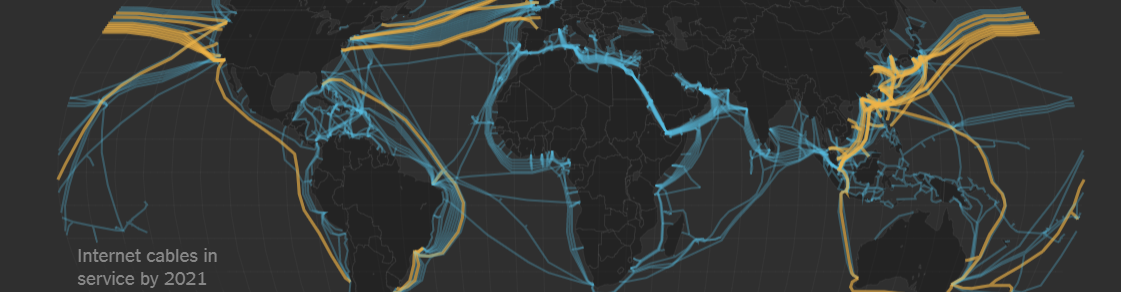

source: https://carbonfeed.org

source: https://carbonfeed.org