Jillian Weise, a poet and disability rights activist, has a refreshingly acute view on the human body and technology – approaching the celebrated movement of biohacking and the discussion on human cyborgs from a perspective of a person with disability, Weise has come up with a term tryborg to distinguish the optional, even hobbyist use of technology from necessary [1]. What Weise brings forward is the truth and reality of people with various disabilities, and the reliance on technology in everyday lives without a chance to opt-out from the latest tech gone out of fashion. “When my leg suddenly beeps and buzzes and goes into “dead mode” — the knee stiffens; I walk like a penguin — the tryborg is alive without batteries” [2]. It cannot be more stressed and obvious – there are people who rely and depend on technology for functions non-disabled people rarely consciously think about.

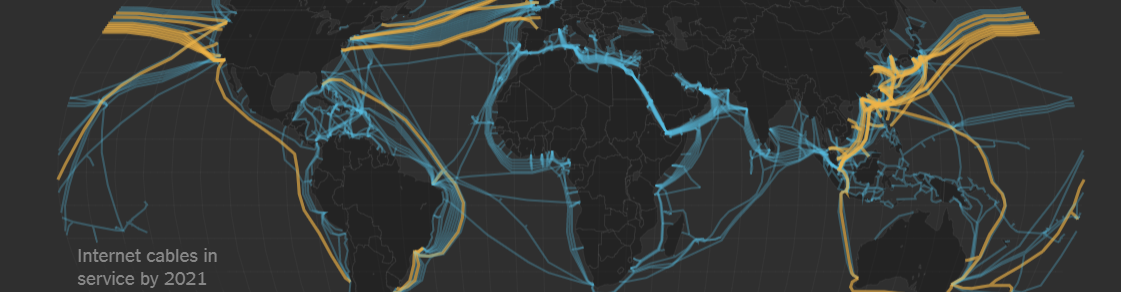

Between the endless data stream on the Internet cables and the pixels of media content, there are layers of technology and code, seemingly transparent and only becoming visible when something glitches, breaks off, fails. And the odds are that they will fail more often if you are a person with a disability. Those technologies are not only the ever-changing devices used for accessing the Web but also interfaces that come into endless forms and colors, following the newest trends or submitting to lack of money and time in coding and development.

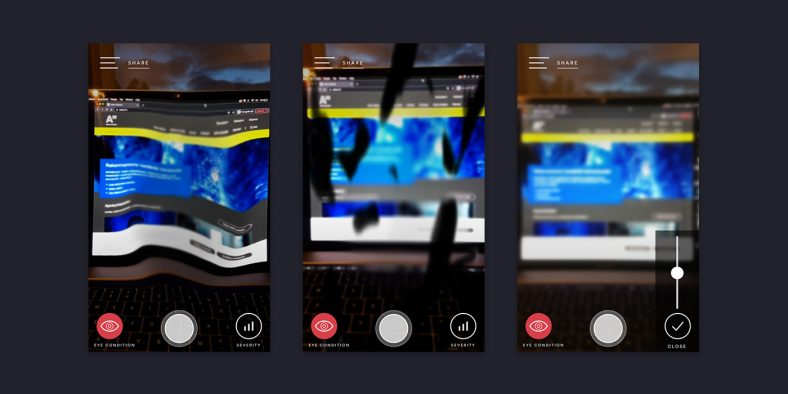

View of Aalto University website with SeeNow visual impairment simulator. Simulation of macular degeneration (1), diabetic retinopathy (2), cataract (3).

To challenge the prevailing notion of the ideal media audience as being non-disabled, Jillian Weise recently held an online event specifically crafted for an audience of deaf members [3]. It’s an act of looking beyond an imaginary of a monogamous mass of entities and online presence, and into more humane realities. But can such a performance fuel a conscious attitude for designers, businesses, and governments to take into account the invisible, but obviously diverse audience?

Digital divide is relevant not only on a global scale but also within local societies, with uneven opportunities, access to and accessibility of the technology. More than 18% of the world’s population suffer from a variety of disabilities, and the general level of Internet access for persons with disabilities is much lower than for the rest of society [4]. And while the Internet possesses a possibility of inclusion and opportunities for the community, the most widely-used hardware, software, and Web content vary considerably in their accessibility to people with a range of disabilities [5]. The Internet can pose opportunities for people with hearing and walking impairments to ease their daily tasks or induce socializing but exclude and marginalize those with visual or cognitive impairments.

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) has developed Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) to help remove the barriers and create services and technology that are broadly accessible [6]. Accessibility, in this case, means that websites, digital products, and technologies are built in a way to be accessed and used by persons with various disabilities – visual, auditory, physical, and cognitive disabilities, that often means giving up the latest hype and visual trends for deliberate accessibility, clear affordances, and an extra time and precision for coding. While the guidelines are not mandatory for the private sector, the EU has developed a Web Accessibility Directive to improve public sector websites and digital products. Recent research in Sweden shows that the focus on visual and sensory impairments in policies and standards for accessibility has improved the experience and use of interfaces for the respective groups, but there are no clear methods or understandings on the design process for accessibility for those with cognitive impairments [7].

Dependence on online services and media is now ever-increasing in business, entertainment and governance, and digital products make way for easier and more dynamic daily lives. Internet access is linked to income, mental health, and social capital [5], therefore the lack of it can lead to socioeconomic disadvantage. And at the same time Internet technologies and products hold a huge potential for reducing the inequalities of people with disabilities, if only they are kept in regard when designing the services and products. If only the devices, digital services, and digital products are usable and worthwhile regardless of who is the person using them. Or as Jillian Weiss’s online performance suggests, designed for people with disabilities in the first place, because those without disabilities will still have the odds on their side.

[1] Jillian Weise, Common Cyborg, In: Disability Visibility, ed. Alice Wong, 2020, p.63-74

[2] Jillian Weise, The Dawn of the Tryborg, 30.11.2016. URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/30/opinion/the-dawn-of-the-tryborg.html

[3] The Cyborg Jillian Weise Hosts A Different Kind of Internet Event, 18.09.2020. URL: https://occhimagazine.com/the-cyborg-jillian-weise-hosts-a-different-kind-of-internet-event/

[4] Vicente, María Rosalía, López, Ana Jesús, A Multidimensional Analysis of the Disability Digital Divide: Some Evidence for Internet Use, In: Information Society. Jan/Feb2010, Vol. 26 Issue 1, p48-64.

[5] Kerry Dobranskya, Eszter Hargittai, Unrealized potential: Exploring the digital disability divide. URL: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2016.08.003

[6] WCAG 2.1. at a Glance, URL: https://www.w3.org/WAI/standards-guidelines/wcag/glance/

[7] Stefan Johansson, Jan Gulliksen, Catharina Gustavsson, Disability digital divide: the use of the internet, smartphones, computers and tablets among people with disabilities in Sweden, In: Universal Access in the Information Society, 7.03.2020, URL: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10209-020-00714-x