I remember very well when in 2013, Facebook opened its first data center outside of the US in Luleå, a northern city in Sweden. It was in all the big news channels. One of the largest and most impactful social media corporations chose Sweden!

For Luleå, the deal with Facebook was a great advertisement for the city. One of the world’s most influential corporations chose to put its facilities there. Data as a product has the appearance of modernity, innovation, high-technology, creativity and in this case, green energy. It goes well with the way Sweden as a nation wants to market itself. Most news articles were written in a weirdly proud manner. The primary reason stated by Facebook was the natural cooling of the servers, provided by the cold climate, and the science magazine Forskning och Framsteg wrote an article jokingly named “This is where your likes are cooling down” (1). I remember spontaneously feeling proud as well. We Swedes are raised with a hate/love relationship to the USA. We love to feel better than the Americans, to look down on them for their capitalist, openly class dividing society structure. But we also watch mostly TV series and movies from Hollywood and think that English is much cooler than Swedish. Secrectly, we all want to move to New York, LA or San Francisco and pursue the American dream. We are sold the idea of a service society, where machines do the dirty work and we can sit back and enjoy our touch screens and fancy clothes.

That dream, however, soon fades if one leaves the big cities. Up until a few decades ago, Sweden was an industrial country, with people working in factories, farms, forests and mines. And even though we are pushed to believe that the industrial society died to give birth to the service based society, Sweden’s economy is still based on those old industries. Facebook and other IT companies make a good front page, but the dirtier industries supplying them with material and energy still exist. And this is where Luleå’s history as an industry city becomes interesting.

Luleå has largely flourished because of the iron mines in Malmberget close by, where Luleå has served as the harbour for exportation of iron goods since late 1800s. The municipality now consists of 77000 people and the city hosts one of Sweden’s leading technical universities. In the meantime, the mining town Malmberget is literally collapsing. The mine has created a 200 meter hole in the ground, constantly growing and swallowing buildings and roads. This has caused the city to expand in new directions and buildings are being moved away from the hole’s edges. In the future, Malmberget will not exist in the place where it is today.

The hole in Malmberget municipality, called Gropen in Swedish.

The mine is utilised by state owned corporation LKAB, which also runs the world’s largest underground mine in the inland city Kiruna (see map below). There, the effects of the mining are even bigger. The whole city of Kiruna is now being moved to a new location since the current one is collapsing. Some buildings are moved, but most of the city will be built completely from scratch to house all the mine workers and other citizens. The new city is said to be financially, socially and environmentally sustainable (2). Kiruna’s new city center in the front, with the mine visible in the far left.

Kiruna’s new city center in the front, with the mine visible in the far left.

Meanwhile, the ecological impact of the mining industry next door is non-reparable. Mining disrupts the landscape and leaves open wounds in the ground. There is always a risk of toxic contamination of fresh water and lakes. The mining industry in Sweden stands for 10% of the CO2 emissions of the country. The indigenous people of the Nordics, the Sami people, have historically and in the present fought against the mining industries since the effects for them can be loss of land, contamination of fresh water and reindeer routes from summer to winter pasture land being cut off (3). Still today, Sweden’s liberal mineral laws permits foreign companies to exploit land without the owner’s permission. The UN have critiqued Swedish governments for not doing enough to protect the indigenous people and their rights to their land (4).

Kiruna at the top and Luleå at the lower right on Google Maps.

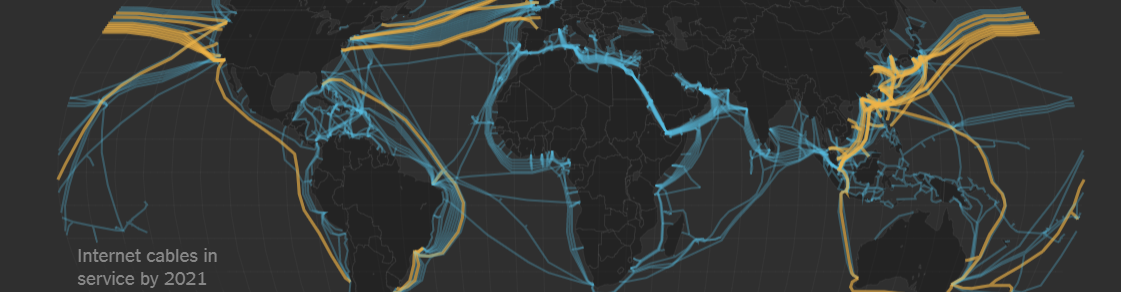

Facebook is now planning to double the size of their data center in Luleå, making it 100,000 sqm. The center is purely driven on water energy, according to Facebook. It directly or indirectly gives full time work for 400 people per year, compared to LKAB who employs around 4000 people in Sweden, with a majority working in the northernmost regions, and indirectly provides work for thousands more through related industries. Sweden’s iron mines jointly produces 90% of the iron in Europe.

Some journalists raised the concern that data centers wouldn’t be able to replace the traditional industries, such as mining and forestry, when it comes to employing large numbers of people. Others have claimed that Facebook is just the first of many data companies that will open centers in northern Sweden, thus leading the way for more work opportunities in the future. But how many jobs can this sector actually produce, and especially in relation to its high energy consumption? Will it be possible for all those data centers to run on water energy? Probably not.

As stated previously on the blog, new media infrastructures are often built on top of existing infrastructures. The data center is no exception. In 1910-1915, a large power plant was built in Lule älv, a river ending in Luleå, to be able to replace some of the coal imported from Europe. But the water flow was too high during Spring. Eyes fell on the newly inaugurated national park surrounding Stora sjöfallen, at the time one of Europe’s biggest water falls. The decision was taken from the government to exclude the water fall from the national park so that it could be dammed, with the consequence that the water flow in the river could be controlled like a tap. The Sami people who fished in the area, and who’s reindeer lands would be put under water, were not asked for permission. If the same decision was taken today, it would lead to massive demonstrations from the public (5). I have been at Stora sjöfallet myself. It is a large silent lake with a small flow of water coming down the water fall.

Surely it isn’t Facebook’s fault that those precious nature resources were destroyed a hundred years ago, and one can argue that the mining industry is necessary for providing the world with minerals. But the societal structure that killed Stora Sjöfallet at the beginning of the century is still working its magic, but now on a global scale. With a promise of work opportunities, multinational corporations are allowed to exploit land and energy resources not just in developing countries, but also in Sweden, whether they are producing minerals or data. Only a tiny portion of the capital produced goes back to the local inhabitants, and even less to the indigenous people. Those mines provide material that is necessary for computers, phones, cables, etc to exist in the first place. So Facebook’s “clean energy footprint” is not so clean after all. But perhaps, if we continue down this path of environmental destruction, the world will look much like the inside of a data center in the end. Lots of blinking machines, but no life.

Facebook’s data center in Luleå, Sweden.

Further readings in English:

http://samer.se/4623

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/dec/02/kiruna-swedish-arctic-town-had-to-move-reindeer-herders-in-the-way

Sources (in Swedish):

https://fof.se/tidning/2017/1/artikel/har-svalnar-dina-likes

https://hallbartbyggande.com/det-nya-kiruna-en-hallbar-modellstad-tar-form/)

https://www.naturskyddsforeningen.se/nyheter/gruvindustrins-gruvligaste-effekter

https://sverigesradio.se/sida/artikel.aspx?programid=2054&artikel=4289211)

http://ottossonochottosson.se/blog/reportage/historien-om-ett-vattenfall/

https://www.lkab.com/sv/SysSiteAssets/documents/publikationer/broschyrer/det-har-ar-lkab.pdf

Infragraphy is a compilation of critical student artworks and short essays dealing with the materialities of media technologies and their environmental implications. The volume presents artworks and texts from the course ‘Media and the Environment’ in the Fall of 2020 at the Department of Media, Aalto University. The course is a series of scholarly readings about and around the themes of media including media’s relations and impacts on the so-called Anthropocene, thermocultures of media, ecologies of fabrication, media and plastics, Internet of Things, Planned Obsolescence, e-waste, and media’s energetic landscapes. A key approach of the course is to introduce artistic methods and practices that could address emerging media materialities. The student artistic outputs are presented in a final exhibition.

Infragraphy is a compilation of critical student artworks and short essays dealing with the materialities of media technologies and their environmental implications. The volume presents artworks and texts from the course ‘Media and the Environment’ in the Fall of 2020 at the Department of Media, Aalto University. The course is a series of scholarly readings about and around the themes of media including media’s relations and impacts on the so-called Anthropocene, thermocultures of media, ecologies of fabrication, media and plastics, Internet of Things, Planned Obsolescence, e-waste, and media’s energetic landscapes. A key approach of the course is to introduce artistic methods and practices that could address emerging media materialities. The student artistic outputs are presented in a final exhibition.

INFRAGRAPHY Volume 2. is a compilation of critical student artworks and short essays dealing with the materialities of media technologies and their environmental implications.

INFRAGRAPHY Volume 2. is a compilation of critical student artworks and short essays dealing with the materialities of media technologies and their environmental implications.