Glossy black-boxed

Only once things fail, then we start thinking about their complexity and become aware of how much the tech objects that surround you are glossy black boxes, designed to appear simple and hide the enormous system that lies behind the object and stays far from our eyes. [1]

The whole world of media wants us to see its LED-luminescent and metal-polished side, but it is obscure in every other direction: the management of data signals arriving at our devices is a secreted activity; the production of the hardware is a story never told by the very firms, but only by journalists fighting for human and environmental causes; electronic waste is more of a taboo that both the big tech companies and the developed society do not want to deal with.

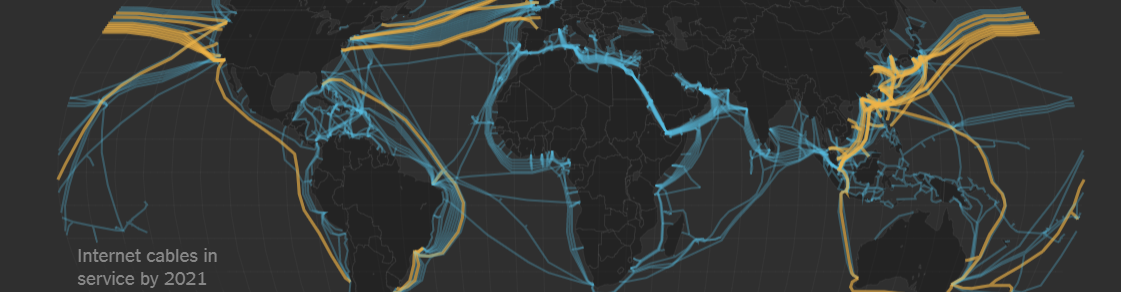

However. as Jussi Parikka argues, all these activities are not theoretical, but material [2]: data centers, data cables, coltan mines causing natural depletion in Central Africa, tech industries based on labor exploitation in China, e-waste landfills, and processing plants in Eastern Europe [3], they are all physical realities that shape entires societies. Taking all this dirt into account and using this as perspective, privilege is the possibility of looking at the result, but not the process.

Will to repair

If the single contemporary citizen has long-lived an imbalanced relation of power with companies, about their production methods and ethics, that could only be won through political pressure, he or she has always been able to take a little revenge through maintenance and mending. However, during the last twenty years, this has been made impossible or inconvenient by tech companies.

The activity of repairing has always been an important task throughout the history of humanity: resources have always been limited and the process of mending could be learned. In the last decades, we, the western privileged who have not seen the natural damages and the human exploitation, have been living in the illusion that resources were illimited and overall cheap, and we never learned how to repair our smartphones, computers, or whatsoever.

This has not happened for pure idleness, but a series of reasons [4]:

- Companies do not provide customers with software or adequate information for maintenance or repairing. If people start autonomously to deliver self-taught technical information, companies usually try to oppose, like Apple with iFixit. [5]

- Often companies do not sell the components either to companies or to non-official repair centers.

- Official repair centers are often so expensive that it is more convenient to buy the new version of the product.

Furthermore, if the life-guaranteed product would give a proper reason for the mending, programmed obsolescence conveys a renunciative attitude. In the era of e-waste, nobody would repair something that is made to break.

Right to repair

However, times are changing. People are now meeting in repair cafés [6]: there is awareness around these themes and organizations like The Repair Association (TRA) have been fighting for the electronics right to repair, obtaining some successes [7], even though big-techs try to remain black-boxed since people could hurt themselves while repairing their smartphones or hacker could have easier access to key information. [8] Of course, both of these argumentations have been found inconsistent, a façade for economic interests that is not working so well anymore. Indeed, knowledge is a form of power and, since tech firms have become important actors within the geopolitical system, the democratic citizen must ask for his right of knowledge, in order to be able to work out alternatives from the bottom.

–

Notes:

[1] Bruno Latour, Where Are the Missing Masses? The Sociology of a Few Mundane Artifacts, in Shaping Technology-Building Society. Studies in Sociotechnical Change, Wiebe Bijker and John Law, MIT Press (1992)

[2] Jussi Parikka, Dust and Exhaustion: The Labor of Media Materialism, Arthur and Marilouise Kroker (2013)

[3] Bulgaria Opens Largest WEEE Recycling Factory in Eastern Europe, Ask-eu.com (12th July 2010)

[4] Karen Turner, Apple wants to kill a bill that could make it easier for you to fix your iPhone, The Washington Post (17th June 2016)

[5] Kyle Wiens, iFixit App Pulled from Apple’s App Store, iFixit (29th September 2015)

[6] Sally McGrane, An Effort to Bury a Throwaway Culture One Repair at a Time, The New York Times (8th May 2012)

[7] Jason Koebler, Internal Documents Show Apple Is Capable of Implementing Right to Repair Legislation, Vice (28th March 2019)

[8] Jason Koebler, Apple Is Telling Lawmakers People Will Hurt Themselves if They Try to Fix iPhones, Vice (30th April 2019)