Internet of Things (IOT)

An increasing number of devices are electronic and networked with each other and connected to the Internet. Radio transmitters connected to the devices collect, identify data via compatible networks, and communicate with each other. These devices are called IoT, or Internet of Things. According to a broader definition, cyber systems are also called IoTs. It can be defined as a dynamic, i.e. constantly changing and evolving, global network infrastructure, i.e., a network infrastructure in which physical and virtual “objects” have an identity, i.e., identity, physical characteristics, and a virtual personality. Intelligent interfaces, ie user interfaces that can, for example, adapt to the needs of different users or anticipate user activity, transmit information seamlessly between objects and the data network. The goal of development is for IoT to enable people and devices to connect anytime, anywhere, anytime. IoT increases everyday comfort and ease of use and can be used by both society and individual citizens. [1]

photo 1

The devices are characterized by the fact that they can be used to combine anything, such as smart watches, security systems, activity bracelets, smart homes, remote heating devices, airplanes, gates and doors, home appliances, consumer electronics, just to name a few. The Internet of Things consist of a growing list of Intelligent devices that would augment, optimize, and interconnect every aspect of our daily lives. An object, such as a car, electrical appliance, or grocery, can connect directly to the Internet through a computer component that has an IP address. The component can be, for example, a sensor, an RFID chip or a WLAN chip. Sometimes it is sufficient for the object to have an identifier, such as a parcel delivery code or a unique identifier modified from the registration number of the vehicle to enable the object to be identified on the Internet. The object does not then need to be connected directly to the internet. Energy companies have provided consumers with smart meters that provide consumers with real-time information on consumption and energy companies can remotely read meters. The Internet of Things can also be utilized in logistics, in which case, for example, food can be measured ambient temperature in the supply chain, and alerts you if the temperature exceeds or falls below a certain limit. [2]

In recent years, digitalisation has also raised its head in the most traditional fields, and drones, for example, are already used in reindeer husbandry to detect reindeer herds from the air. In Oulu, reindeer herding is being developed under the auspices of IOT technology, and as a result, a Rudolf device was created, which can be used to monitor the health status and location of reindeer through a mobile application. In the future, the technology could even be used to prevent animal diseases and traffic accidents. With Rudolf, tracking even a single reindeer is effortless. [3]

photo 2

Digital applications extend their tentacles everywhere in society. Electronic warfare is also present on the battlefield with ubiquitous armored vehicles at the forefront of the attack, in support of the air operation and as part of the reconnaissance system on land, sea and air. Electronic warfare inquires and disrupts enemy systems and protects its own forces from the effects of enemy electronic warfare. [4]

In 2020, the number of connected devices per person was 6.58 and the total number of devices was 50 billion. Smart home appliances in households is highest in China, second highest in the US and third highest in the EU8. [5] Every second 127 new devices are added connected to the internet.

The Internet of Things as a concept is often dated to Mark Weiser’s work on ubiquitous computing at Xerox Parc in the 1980s and 1990s, 9 and as an actual term is dated to 1999, another pivotal moment in the concept’s elaboration is 2008, the year when Internet-based machine-to-machine connectivity surpassed that of human-to-human connectivity.

Behind the screen

Household objects that are currently being transformed into electronic technologies is not only lengthening, but also beginning to constitute a categorically different media “ecosystem.” How might an attention to these material and environmental effects provide an opportunity for generating new areas of environmental intervention in relation to sustainable media? We can no longer just stare at our own equipment but we must also try to see it from a broader perspective. What lies beyond the screen, of how hardware unfolds (avautua) into wider ecologies of media devices, and of how electronic waste may evidence the complex ways in which media are material and environmental?

Energy meters are one example of how recurring access to data about energy consumption is meant to influence behaviour and bring about a reduction in energy use. Attempts have been made to study the routes of how waste is travelling across United States by adding electronic tags into the trash items and tracking their journey.

“Thingification” is an overtly material approach to the previously “virtual” concerns of digital media, and is an industry strategy that is meant to expand the reach, capacities, and economic growth of the Internet. Thingification may make any number of activities and practices within our everyday lives more efficient, sustainable, and safe

Rethingification does not simply involve mapping out the static stuff that constitutes any particular media technology, but rather requires attending to the ways in which things attract, infect, and propagate mediatized relations, practices, imaginaries, and environments. A critical and material media studies might then begin to develop methods and modes of practice that adopt an experimental set of approaches to re-thingification.

Re-thingification of things

IoT has a lot of potential, but its information security is weak or almost non-existent, as systems and devices have been developed for the market quickly and often without compromising on information security requirements. Another challenge is the lack of concrete preparedness for the potential threats to social systems posed by the IoT. For example, in industrial, transport and energy production sites, poorly protected IoT activities can cause significant damage, the effects of which can extend to society at large. [1]

A society built on a large sector of digital information networks is vulnerable in many ways. We have got a taste of the lack of information security in an extensive data breach that targeted patient data in Finland. Cyber hacking can do great damage to the lives of individuals and damage the structures of society. Examples include ensuring the security of power plants, electricity networks and water distribution.

Computer hackers, organized crime, and various fanatics form their own war front, with a front line everywhere. Organized crime can afford to buy the best computers and encryption software on the market. This allows drug offenders to exchange information under the noses of authorities with their 128-bit encryption. Breaking such encryption, according to Adams, will take 40 billion years from a Cray supercomputer. So figuring out the code is laborious even for the U.S. security agency NSA, which is said to have a nearly three-acre cave full of supercomputers. In his book “The Next World War” (1998), James Adams says that high technology means not only superior military power but also a very high degree of vulnerability. For example, a touring man managed to black out four U.S. air control centers while burning a dead cattle in a pit they dug. Below happened to be an important fiber optic cable. [6]

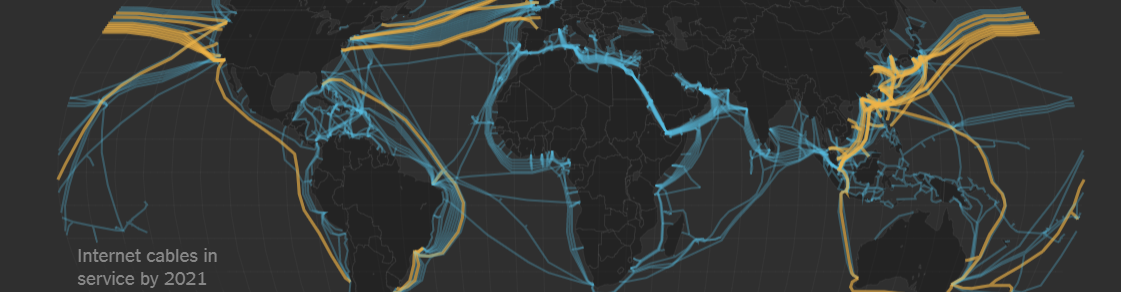

photo 3

As one text collected in The Crystal World Reader, and drawn from the US National Mining Association, remarks, there are at least sixty-six individual Minerals that contribute to a typical computer, and “it should be evident that without many Minerals, there would be no computers, or Televisions for that matter. The minerals needed to build computer networks are not an inexhaustible natural resource. Digital waste is also something that cannot be ignored in the debate on digital information networks.

What do these distributed arrangements and materialities of computation enable, what processes and relations do they set in play and require, and what new environmental effects do they generate? The actual and anticipated debris of electronics might provide one way that we could tune into these material processes to develop practices that speculate about material politics and relations in order to be less extractive and harmful. But this approach would require a re-thingification of things, particularly the Internet of Things.

Reference:

Jennifer Gabrys, “Re-thingifying the Internet of Things,” Sustainable Media: Critical Approaches to Media and Environment, eds. Nicole Starosielski and Janet Walker, New York and London, Routledge, 2016: 180 – 195

[1] https://peda.net/jyu/it/do/kkv/6kvjvtt/6tth/iotieei2

[2] https://www.ficom.fi/ict-ala/tilastot/iot-esineiden-internet

[3] https://www.dna.fi/yrityksille/blogi/-/blogs/oulussa-porotaloutta-kehitetaan-nb-iot-teknologian-siivittamana

[4] 7https://upseeriksi.fi/koulutusohjelmat/maavoimienko

[5 ] The Mobile Economy 2020, GSMA

[6] https://www.oulu.fi/blogs/seuraava-sota-on-digitaalinen

photos:

1. https://peda.net/jyu/it/do/kkv/6kvjvtt/6tth/iotieei2/iotieei2/e

2. https://www.dna.fi/yrityksille/blogi/-/blogs/oulussa-porotaloutta-kehitetaan-nb-iot-teknologian-siivittamana

3. https://www.digital-war.org/blog