Lately, when I’ve suggested to others that we should print posters to promote an event or for spreading information, they have replied “but should we really waste paper and ink like that? Can’t we just market this via social media channels?” This question baffles me for several reasons. Here’s a few:

1. Information and marketing through social media is only accessed by people who use those channels. Algorithms used by e.g. Facebook or Instagram will limit the spreading even further, since the content will only be shown to people who the algorithm “believes” have an interest in that particular post.

2. If all political/artistic/activist/non-commercial content is moved to social media and the internet, commercial forces will dominate the physical visual space through advertisement. This shift has already taken place, to a large extent. Public art is, once more, questioned by politicians and twitter celebrities. An example is Swedish municipality Sölvesborg, where nationalist party Sweden Democrats, in coalition with two conservative parties, are in power. They have now made an official statement that they will “cut down on the purchases of “challenging contemporary art” in favour of timeless, classical art that “will appeal to the vast majority of citizens”, according to municipal commisioner Louise Erixon (my translation). The example they use for unwanted, challenging art is graphic artist Liv Strömqvist’s drawings of menstruating women, that were showcased as public art in the Stockholm metro system [2]. This statement has sparked a huge, nation wide debate about public art and its purpose, but the debate about advertisement in public space is still missing. If the “menstruation art” had been exchanged for a screen with commercial messages, no politician or citizen would have written lengthy texts about it, because it has been normalised.

Photo of Liv Strömqvists “menstrual art” in the metro station Slussen, Stockholm. Credit: argaclara.com

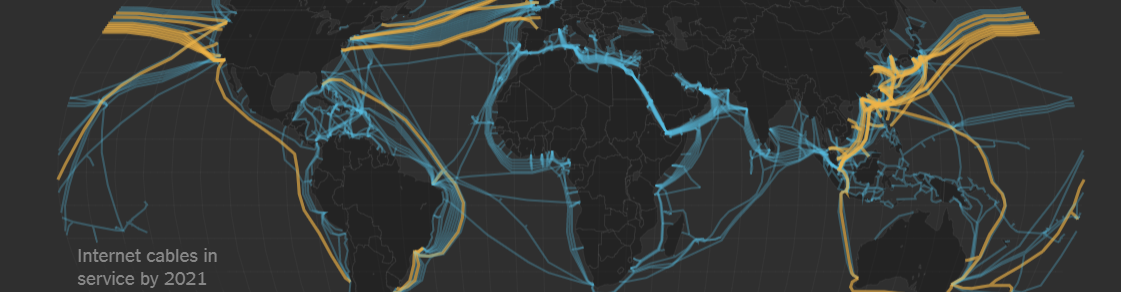

3. Is reading on a screen instead of paper really better for the environment? Sean Cubitt urges us in Ecologies of Fabrication to use the term ecomedia, writing: ‘the study of the intermediation of everything, cannot rest on individuality but must work on the level of community, communication and communion’ (p.166). This poses an interesting challenge on evaluating the use of screens – assessments on reading on a screen vs paper on an individual level have been done and points partly in favour of the screen, but does that mean it’s sustainable for everyone to have their own personal smart device in order to look at art, find events to go to, look at maps, talk to friends, read the newspaper, etc? Ecomedia isn’t part of the tool kit when a life cycle assessment is done for a product*.

The discussion on print vs screen needs to take into account the wider scope of production and energy usage on a global scale, the use of public space and the physical vs the virtual.