INFRAGRAPHY Vol. V. Spring 2021

Infragraphy is a compilation of critical student essays and artworks dealing with the materialities of media infrastructures and their environmental implications. The volume presents the outcomes from the course ‘Archaeology of Media Infrastructures’ in the Spring of 2021 at the Department of Media, Aalto University. The course is a series of scholarly readings on media infrastructures including the themes of deep time, network connectivity, Artificial Intelligence, digital labor, water resources, energy consumption, and critical infrastructures. These readings were followed upon with intense online classroom discussions and debates. A new approach in Spring 2021 was to introduce artistic methods and practices that could address emerging media materialities primarily focused on infrastructure. The related student artistic outputs are presented in a companion virtual exhibition.

This fifth volume of Infragraphy presents themes ranging from media aesthetics, cloud materialities, media temporalities to human-machine relations. Francesca Bogani Amadori explores the temporalities of media infrastructures in _Infrastructural Reality_Digital Time_Labor Time. Amadori seeks to make visible how malleable our perception, and experience of time is, and how we are vulnerable to the information of the “infrastructural reality”. In (An)aesthetics of the Surface, Liga Felta examines aesthetics of media technologies. Felta especially considers the prevailing technological imaginaries and pleasure derived from aestheticized representation as a means of hiding the slow violence of media technologies. In Human-Machine Relations, Alicia Romero Fernandez experiments with media and behavior with the dumb-phone project, where a placebo smart-phone made of porcelain is used to probe into our entrenched relations with connectivity. In Free the Clouds Federico Simeoni presents an investigation of the iconographic strategy of cloud infrastructures. By a series of collages, Simeoni unravels the layered structure of the Cloud metaphor. Finally, in Contemporary Mandala, through the deliberate re-composition of a sacred symbol, Tuula Vehanen analyzes the visual representation of the Internet. In Vehanen’s depiction, concrete machinery has replaced the symbolism of a traditional sacred image.

Samir Bhowmik

24 April 2021, Helsinki

Virtual Exhibition: https://www.aalto.fi/en/news/deep-surfacing-archaeology-of-media-infrastructures-spring-2021-course-exhibition

The Aesthetics of Destruction

During the last decades, the concern on the health of the ocean has grown. We have been using it as the global dumpster, filling it with trash and plastics, and now we know that the water contains micro-plastics that will never disappear.

However, why are we so concerned about the ocean if it is not the human habitat? There are many forests logged and many landscapes destroyed by mining activities every day. It seems to be more accepted, maybe because the images we get from land are not that shocking, since we are used to its destruction. Moreover, the imagery around the ocean has been very poeticized and mysterious, so we feel more guilty when hurting it.

Photo by Ed Kashi, National Geographic Image Collection.

The fact is that all the planet is connected, so whatever concerns us will affect the rest of it. As Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler explain in the text Analysis of an AI System, the first transcontinental cables that served as communication bridges from land to land were recovered in rubber so they could function [1]. This rubber was known as gutta-percha, and it was obtained from the Palaquium Guttatree (nowadays extinct) by native workers in dangerous conditions.

Landing of an Italy-USA cable, January 1925.

In this case, transcontinental communication damaged both the seafloor and the forests, affecting both the marine and the land ecosystems. The cables that connect two continents also connect two worlds: the marine with the terrestrial. We, as humans, perceive these changes as images that change the aesthetic perceptions that we have in the different environments.

Ossi Naukkarinen defines Aesthetic Footprint as the aesthetic impact of any object or action on the environment [2]. The concept is subject to the cultural and evaluative values of each individual. Depending on that, the aesthetic experience can be positive or negative for the self.

In the text Environmental Aesthetics in the Age of Climate Change, Matthew R. Auer writes about how people’s appreciation of the environment change, at the same time that climate change is altering the environment [3]. There are different theories relating to that. Some defend that the adaptability of the human will help societies to appreciate the new forms of the surroundings. But, others maintain that the world will become full of ugliness and negative aesthetic experiences. Moreover, he talks about the moral pressures and how the people will have an increasing feeling of guilt for the changes in the environment.

References:

[1] Crawford, Kate; Joler, Vladan. Anatomy of an AI System (2018).

[2] Naukkarinen, Ossi. Aesthetic Footprint (2011).

[3] Auer, Matthew R. Environmental Aesthetics in the Age of Climate Change (2019).

~ Alicia Romero

Simply Opaque

Minimalism

In the last years, minimalistic design has been facing a great decline in its appeal to both designers and consumers. The shift from this 50-year-old trend has philosophical roots and it is related to the way designed objects mediate and filter reality.

Minimalistic design is often the result of a functionalist approach. Every finalized element has been passing through a series of selecting processes and all the rest has been cleared away for it has been labeled as irrelevant. In other words, to make the object interface or surface as simple as possible, the designer reduces reality into a metaphor with limited prescribed ways of interpretation and action. As a result, the sometimes over-simplified external layer has no clues of the technological complexity hidden behind and within itself. The simplicity of contemporary design is a property of the surface or, using Tommaso Labranca’s words, only a lie. [1]

Veil of Maya

The reason why maximalism is on the rise is to be found in the fact that it respects the complexity of reality, whereas minimalism acts as a filter where accessibility is obtained through opacity. When the general user interacts with an object, he does not need to know what is behind and within it: consequently, a veil of Maya is put on these aspects for the sake of simplicity. Indeed, Mattew Fuller and Andrew Goffey quote Jean Baudrillard’s The System of Objects while asserting that certain recessiveness is often a crucial aspect of the efficacy of certain design objects. [2]

Camouflage

This argumentation can be applied to the entire mediasphere. As the computer scientist Bran Ferren defined it, “technology is stuff that doesn’t work yet,” [3] and the remaining, what is smoothly working and it does not need to be understood by the general user, is consequently infrastructure. [4] Indeed, media infrastructure is deeply characterized by dynamics of obscureness and difficulty of accessibility: as Bruno Latour suggests, any technology that is taken for granted for its near impossibility of failure becomes opaque, [5] since the user is not supposed to understand the mechanisms behind and within the object anymore.

However, this opacity can take shape in different ways. As Fuller and Goffey point out, “black boxing is perhaps too clear a term, for boxes are rather too sharply edged to describe all kinds of operations or practices of mediation.” Sometimes, it is more of a grey “cognitive camouflage” that marks everything that is intended to be uniformly dull and uninteresting, making the process of knowing boring. [2] In other cases, secrecy is deliberately the modus operandi of companies such as Google or Amazon, whose “data centers are information infrastructures hiding in plain sight.” [6]

Maximalism

The more a technology works, the more complex it becomes due to both its intrinsic developments and to the eco-socio-relational implications, since more people are adopting it in their daily life, evolving into infrastructure. The combination of growing complexity and the need for general accessibility generates the necessity of minimalism: reassuring (but not realistic) simple surfaces and interfaces let the users focusing on other issues. Maximalism is then the aesthetic reaction that denounces the limits of this mechanism; whereas media archaeology has the task of discerning structures of power through technological and industrial analysis behind the metaphors and the imaginaries that media companies provide. [6]

–

Notes:

[1] Tommaso Labranca, Andy Warhol era un coatto. Vivere e capire il trash, Roma, Castelvecchi (1994)

[2] Mattew Fuller and Andrew Goffey, Evil Media, MIT Press (2012)

[3] Douglas Adams, How to Stop Worrying and Learn to Love the Internet, The Sunday Times (29th August 1999)

[4] Jamie Allen, Critical Infrastructure, Aprja (28th February 2014)

[5] Bruno Latour, On Technical Mediation, Common Knowledge, #2 (1994)

[6] Jennifer Holt and Patrick Vonderai, Where the Internet Lives from Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski, Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures, University of Illinois Press (2015)

The Gods must be crazy

The film ´The Gods must be crazy´ tells about San tribe living in Kalahari desert, away from industrial civilisation. One day, a glass Coca-Cola bottle is thrown out of an airplane by a pilot and falls to the ground unbroken. Initially, San people assume the bottle to be a gift from their gods, just as they believe plants and animals are, and find many uses for it. Unlike other bounties, however, there is only one glass bottle, which causes unforeseen conflict within the tribe. As a result, Xi, a member of the tribe, decides to make a pilgrimage to the edge of the world and dispose of the divisive object. (1)

The film criticizes the features of Western culture, the lack of community, and the culture of matter. While it ridicules Western culture through comedy, it raises us ethical as well as practical questions: how legitimate is it to take our own internet or culture to other cultural areas, what are the motives for cultural export and digitalization, and what are its implications?

- San

Bushmen

GLOBALIZATION

Globalization has accelerated since the 18th century thanks to advances in transportation and communications technology. Globalization is generally divided into three main areas: economic, cultural, and political globalization. Building the Internet in developing countries affects all three sectors. The Internet and mobile phones have been significant factors in globalization and have continued to create interdependence and economic and cultural activity around the globe. (2)

Globalization means taking on the positive sides of the world, but globalization is also sparking a debate about Westernisation. Democracy, fast food, and American pop culture can all be examples that are considered Western in the world. According to the publication “Theory of the Globe scrambled by Social network: a new Sphere of Influence 2.0” published by Jura Gentium (University of Florence), social media dominates the growing role in Westernization. A comparison to Eastern realities that decided to ban American social media (such as Iran and China with Facebook, Twitter) signifies a political will to avoid the Westernization of their own population and the way they communicate.

Globalization also involves challenges such as global warming, water and air pollution, overfishing and the unequal distribution of raw materials and resources, as well as the mindsets created by colonialist thinking.

In his book The Great Convergence: Asia, the West, and the Logic of One World, Kishore Mahbubani calls for national interests to be balanced with global interests and power to be shared. (3)

EQUALITY

The gender gap is global. In several European countries, two thirds of Internet users are men. In Brazil, men control the Internet with 75 percent of users, in China with 93 percent, and in Arab countries with 96 percent.

The linguistic and cultural gap is also significant. Although English is spoken by only six percent of the world’s population, 80 percent of websites are in English. Thus, for the majority of the world’s population, the majority of the Internet is completely inaccessible or only partially comprehensible. (4)

In some places, only the rich have access to the Internet in developing countries.

Illiteracy is one of the challenges. More than 75% of the world’s 781 million illiterate adults are found in South Asia, West Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, and women represent nearly two-thirds of all illiterate adults worldwide. Sub-Saharan Africa accounts for 64% of the illiterate (2015). (5)

Whether the spread of the internet will increase or eliminate inequality in society remains to be seen.

ECOLOGY

Data centers consume more than 400 terawatt hours of electricity globally, accounting for about two percent of the world’s energy consumption. Emissions are now at the same level as aviation, but by 2025, data center electricity consumption is predicted to double and emissions to be generated more than from aviation.

In addition to energy-efficient data centers, cleaning up digital waste also has an impact on data emissions. In the digital age, less paper may be generated, but even more useless bits are produced. Each of them has a carbon footprint. Files stored in cloud services accumulate the amount of data stored in data centers and increase the carbon footprint. One email with attachments can produce up to 50 grams of carbon dioxide. (6)

The ICT sector has an important role to play in enabling a more climate- and environment- friendly society. (7) It should be possible to build carbon-neutral data centers in developing countries. It is problematic in countries where environmental protection and governance are not even close to European standards.

DIGITAL COLONIALISM

Data centers are currently without a doubt one of the fastest growing industries in the world

Africa has a population of over 1 billion and is expected to grow by more than 2.5% annually, according to UN forecasts. A large portion of the population is young people who have grown up in the digital age but live in one of the least utilized areas of data centers and telecommunications companies in the world. The Asian continent is expected to be the largest data center market by 2021. (8)

Sociologist Michael Kwet (9) warns of the dangers of Silicon Valley’s plans for Africa – in a scenario he calls digital colonialism. According to Kwet, the problem is this: U.S. technology companies are working to control the digital ecosystem and thus the entire transfer of information to the continent. Within a short period of time, it changed into a technological system controlled by a handful of companies

The race to control Africa’s digital market is dominated by US tech giants: Amazon, Google and Facebook, as well as China’s Huawei. (10).

Facebook plans to install a submarine fiber optic cable around the entire African continent. The cable is three times the connectivity capacity of existing submarine cables serving the continent.(11)

DIGITAL DEVIDE

More than one and a half billion people do not have access to the internet, and at least 300 million of them live in Africa. (12)

Africa itself exhibits an inner digital divide, with most Internet activity and infrastructure concentrated in South Africa, Morocco, Egypt as well as smaller economies like Mauritius and Seychelles.

In 2000, Subsaharan Africa as a whole had fewer fixed telephone lines than Manhattan, and in 2006 Africa contributed to only 2% of the world’s overall telephone lines in the world. (13)

As a consequence of the scarce overall bandwidth provided by cable connections, a large section of Internet traffic in Africa goes through expensive satellite links. In general, thus, the cost of Internet access (and even more so Broadband access) is unaffordable by most of the population. According to the Kenyan ISPs association, high costs are also a consequence of the subjection of African ISPs to European ISPs and the lack of a clear international regulation of inter-ISP cost partition.The total bandwidth available to Africa was less than that available to Norway alone (49,000 Mbit / s).

- Internet users in 2015 as a percentage of a country’s population

Africa clearly shows as the largest single area behind the digital divide.Source: International Telecommunications Union

The International Telecommunication Union has held the first Connect the World meeting in Kigali, Rwanda (in October 2007) as a demonstration that the development of telecommunications in Africa is considered a key intermediate objective for the fulfillment of the Millennium Development Goals (14)

A new report calling for urgent action to close the internet access gap suggests that around $ 100 billion would be needed to achieve universal access to Broadband connectivity in Africa by 2030. This is a formidable challenge, as about a third of the population remains out of reach of mobile Broadband signal in Sub-Saharan Africa. The report estimates that nearly 250,000 new 4G base stations and at least 250,000 kilometers of new fiber across the region would be required to achieve the goal. (15)

Bill Gates has stated that the poor do not need computers but basic security such as food, water and health care. For the price of one computer, 2,000 children could be vaccinated against six killer diseases. If developing countries’ debts are not canceled, the G8’s actions will remain empty gestures,” commented Ann Pettifor on the decisions of last summer’s Okinawa meeting on the Jubilee 2000 campaign, under which the DOT Force working group leaves its proposals to leaders of rich countries in Genoa to close the digital divide. (16)

CULTURAL GAP

While there are many benefits to expanding the network, there are also problems to be solved on different continents, with infrastructure and quality standards at the forefront. However, the shortage of skilled labor and ignorance of the need for data center security solutions is expected to be a significant challenge.

The location of data centers on different continents and in different countries poses new challenges, as safety-related legislation and applicable building standards can differ significantly.

The conversion of existing buildings into functioning data centers is a particular trend in developing countries, which from a security perspective, this poses new challenges as well. (8)

OFF-LINE

Shutting down the Internet has been used as a policy instrument. Governments in Tanzania, Chad, Ethiopia and Uganda have used internet switch-offs and social media blackouts as a weapon against a rising opposition, to ensure they restrict the flow of information thereby getting re-elected against the will of voters. The Internet shutdown caused huge losses for example as businesses, government agencies, organizations and web-based operations such as banking, electronic file transfers, e-tax payments were disrupted.

From Caracas to Khartoum, Protesters are leveraging the internet to organize online and stand up for their rights offline. In response, in the past year governments in Bangladesh, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Sudan, Myanmar and Zimbabwe shut down the internet in all or some parts of their countries, perhaps with the hope that doing so would shut off their problems. Governments are increasingly using closures in crisis situations, claiming that they are necessary for public security or curbing the spread of misinformation.

When the internet is off, People’s ability to express themselves freely is limited, the economy suffers, journalists struggle to upload photos and videos documenting government overreach and abuse, students are cut off from their Lessons, taxes can’t be paid on time, and those needing health care cannot get consistent access.

Long internet shutdowns and social media blackouts between January 2020 and February 2021 have been termed “counterintuitive and a violation of human rights” in the digital age, according to social media giant Facebook’s East Africa spokesperson, Janet Kemboi. (17)

references:

(1) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Gods_Must_Be_Crazy

(2) https://en.qaz.wiki/wiki/Globalization

(3) https://en.qaz.wiki/wiki/Westernization

(4) https://www.maailmankuvalehti.fi/2001/3/yleinen/digitaalinen-kuilu-kasvaa/

(5) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_count_to_literacy_by

(6) https://www.telia.fi/yritysille/artikkelit/artikkeli/datakeskukset-ovat-unohdettu-paastojen-lahde

(7) https://puheenvuoro.uusisuomi.fi/rikureinikka/173841-sivilisaation-evoluutio-a-history-of-the-world-in-our-time

(8) https://www.stanleysecurity.fi/siteassets/finland/meista/data-center/tulevaisuus-datakeskus-raportti.pdf

(9) Michael Kwet is a Visiting Fellow of the Information Society Project at Yale Law School. He is the author of Digital colonialism: US empire and the new imperialism in the Global South, and hosts the Tech Empire podcast. His work has been published at The New York Times, VICE News, Al Jazeera, Wired, BBC World News Radio, Mail & Guardian, Counterpunch, and other outlets. He received his PhD in Sociology from Rhodes University, South Africa.

(10) /https://www.dw.com/en/digital-colonialism-cheap-internet-access-for-africa-but-at-what-cost/a-48966770

(11) https://www.tivi.fi/uutiset/facebook-ymparoi-koko-afrikan-kuitukaapeli

(12) https://unric.org/fi/afrikkalaiset-maalaiskylaet-paeaesemaessae-internetis/

(13) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_in_Africa

(14) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_in_Africa

(15) // https://blogs.worldbank.org/digital-development/africas-connectivity-gap-can-map-tell-story

(16) /https://www.maailmankuvalehti.fi/2001/3/yleinen/digitaalinen-kuilu-kasvaa/

(17) /https://allafrica.com/view/group/main/main/id/00076816.html

PHOTO & ILLUSTRATION CREDITS

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_people

- Nairobi Business Monthly

- http://echosante.info/environmental-protection-a-strong-regulatory-framework/

- https://bluetown.com/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_in_Africa

- Empower Africa

afrikka nettikaapeli : https://web.asn.com/en/

The odds of digital inclusion

Jillian Weise, a poet and disability rights activist, has a refreshingly acute view on the human body and technology – approaching the celebrated movement of biohacking and the discussion on human cyborgs from a perspective of a person with disability, Weise has come up with a term tryborg to distinguish the optional, even hobbyist use of technology from necessary [1]. What Weise brings forward is the truth and reality of people with various disabilities, and the reliance on technology in everyday lives without a chance to opt-out from the latest tech gone out of fashion. “When my leg suddenly beeps and buzzes and goes into “dead mode” — the knee stiffens; I walk like a penguin — the tryborg is alive without batteries” [2]. It cannot be more stressed and obvious – there are people who rely and depend on technology for functions non-disabled people rarely consciously think about.

Between the endless data stream on the Internet cables and the pixels of media content, there are layers of technology and code, seemingly transparent and only becoming visible when something glitches, breaks off, fails. And the odds are that they will fail more often if you are a person with a disability. Those technologies are not only the ever-changing devices used for accessing the Web but also interfaces that come into endless forms and colors, following the newest trends or submitting to lack of money and time in coding and development.

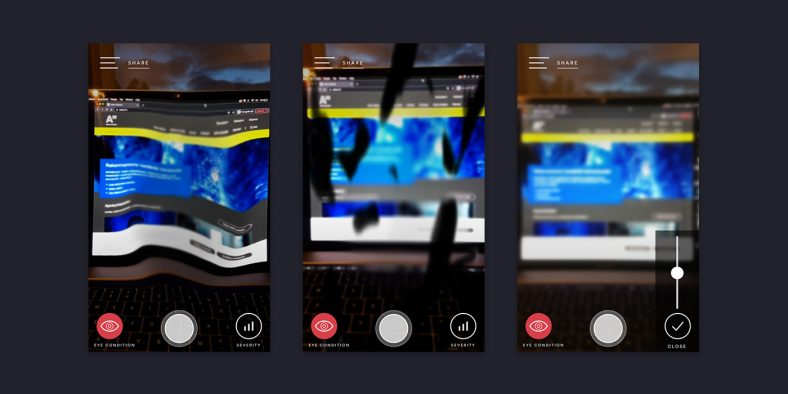

View of Aalto University website with SeeNow visual impairment simulator. Simulation of macular degeneration (1), diabetic retinopathy (2), cataract (3).

To challenge the prevailing notion of the ideal media audience as being non-disabled, Jillian Weise recently held an online event specifically crafted for an audience of deaf members [3]. It’s an act of looking beyond an imaginary of a monogamous mass of entities and online presence, and into more humane realities. But can such a performance fuel a conscious attitude for designers, businesses, and governments to take into account the invisible, but obviously diverse audience?

Digital divide is relevant not only on a global scale but also within local societies, with uneven opportunities, access to and accessibility of the technology. More than 18% of the world’s population suffer from a variety of disabilities, and the general level of Internet access for persons with disabilities is much lower than for the rest of society [4]. And while the Internet possesses a possibility of inclusion and opportunities for the community, the most widely-used hardware, software, and Web content vary considerably in their accessibility to people with a range of disabilities [5]. The Internet can pose opportunities for people with hearing and walking impairments to ease their daily tasks or induce socializing but exclude and marginalize those with visual or cognitive impairments.

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) has developed Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) to help remove the barriers and create services and technology that are broadly accessible [6]. Accessibility, in this case, means that websites, digital products, and technologies are built in a way to be accessed and used by persons with various disabilities – visual, auditory, physical, and cognitive disabilities, that often means giving up the latest hype and visual trends for deliberate accessibility, clear affordances, and an extra time and precision for coding. While the guidelines are not mandatory for the private sector, the EU has developed a Web Accessibility Directive to improve public sector websites and digital products. Recent research in Sweden shows that the focus on visual and sensory impairments in policies and standards for accessibility has improved the experience and use of interfaces for the respective groups, but there are no clear methods or understandings on the design process for accessibility for those with cognitive impairments [7].

Dependence on online services and media is now ever-increasing in business, entertainment and governance, and digital products make way for easier and more dynamic daily lives. Internet access is linked to income, mental health, and social capital [5], therefore the lack of it can lead to socioeconomic disadvantage. And at the same time Internet technologies and products hold a huge potential for reducing the inequalities of people with disabilities, if only they are kept in regard when designing the services and products. If only the devices, digital services, and digital products are usable and worthwhile regardless of who is the person using them. Or as Jillian Weiss’s online performance suggests, designed for people with disabilities in the first place, because those without disabilities will still have the odds on their side.

[1] Jillian Weise, Common Cyborg, In: Disability Visibility, ed. Alice Wong, 2020, p.63-74

[2] Jillian Weise, The Dawn of the Tryborg, 30.11.2016. URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/30/opinion/the-dawn-of-the-tryborg.html

[3] The Cyborg Jillian Weise Hosts A Different Kind of Internet Event, 18.09.2020. URL: https://occhimagazine.com/the-cyborg-jillian-weise-hosts-a-different-kind-of-internet-event/

[4] Vicente, María Rosalía, López, Ana Jesús, A Multidimensional Analysis of the Disability Digital Divide: Some Evidence for Internet Use, In: Information Society. Jan/Feb2010, Vol. 26 Issue 1, p48-64.

[5] Kerry Dobranskya, Eszter Hargittai, Unrealized potential: Exploring the digital disability divide. URL: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2016.08.003

[6] WCAG 2.1. at a Glance, URL: https://www.w3.org/WAI/standards-guidelines/wcag/glance/

[7] Stefan Johansson, Jan Gulliksen, Catharina Gustavsson, Disability digital divide: the use of the internet, smartphones, computers and tablets among people with disabilities in Sweden, In: Universal Access in the Information Society, 7.03.2020, URL: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10209-020-00714-x

Notes on labor and inequality in infrastructures

Much perspectives come in place while writing this note that comes as a reflexive and self-awareness text on many issues such as my cognitive sovereignty, my perception and understanding of time in a present scale also in its multiplicity and implications, the understanding that my every decision or action is, undeniably, tied to my context and agency society gives me, and comes with consequences whether I can witness them or not which talks about certain privileges I came to have at this stage of my life, but could easily not have if having not taken certain actions that I know sums into the chain of negative footprints, like getting two flights to get here, plus the amount of clicking those tickets implied since plenty other flights were canceled before due to the ongoing pandemic.

As a South-American woman in my early 30s being a student in Helsinki, it is inevitable to compare infrastructure and systems and their affect on the non-standard citizens. The first obvious contrast with my previous infrastructure reality is the facilitating presence of proper, digitally connected, public transportation – that I came to discover that as in any other place has its spotless functionality grounded on location, more on that later. Second, and almost on an overwhelming side, I came to experience the huge reliance on digitalization which goes from mundane tasks, such as getting the metro on time to more important matters as bank services access. Everything is profoundly connected to the ID authentification system, which not only implies a matter of public control but also a powerful border setter. [1]

Digital infrastructures, such as those, hold the power to create huge class gaps; frame as a simple understanding of differentiation between those who are part of the digital systems and those who are not. The reality is that there is a more complex creation of classes based on the accessibility to the digital infrastructure and requirements of certain devices that fit the system. As a result, there are different sorts of citizens: lawful citizens, temporal citizens, outcast citizens, non-citizens, international students – which somehow belong to their own gray area, temporal international students, unlawful citizens, illegal subjects, and so on.

By exploring this phenomenon we understand that the infrastructure itself is labeling us, restricting our relational identities and agency in the society frame, fitting us in specific spheres of action. This naming affects the capacity of access to certain services and benefits, such as banking loans or housing leases, affecting also the quality of services provided like public transportation or verified phone lines. Therefore affecting the daily ways of reaching and communicating, distorting physically the perception of time, creating a significant difference between the time of the digital lawful citizens and those, us, on the outside or gray areas.

Consequently, we can discuss that the infrastructure builds upon cognitive capitalism, particularly, on certain types of individuals if we take into account that those out of the system tend to live further from work and city centers, constantly expending more time waiting for their transport, moreover, out of lack of infrastructure, many have to live in remote areas to be close to work in Helsinki, there are just two railway corridors from the core area along the main railway line and the coastal line [2]. Another key aspect of the affects on the cognitive state of digital infrastructure and infrastructure on individuals is the impossibility to access online services and have to invest more time on phone ques or presential meetings for any required matter, there is no time to rest, no infrastructure to make it possible neither.

Time is scarce and the limited that some can access is manly to be able to cover for already invested time -say returning for those borrowed waiting hours. We are again in an industrial-ish era working around the clock, not even being able to make the most out of the minute, minutes feels like seconds, but at the same time can feel like days in a restless laboring routine [3], and big companies are taking advantage of this digital class gaps turning the demand of the digitalized ones into the restless routine of the outsiders by turning overnight their lives into a 24/7 shifts. We can see for example the case of the “megacycles” of Amazon which runs on unthinkable hours, not considering traveling times, other living responsibilities nor resting times, coming to be a maximum degree of digital labor and for that matter “boiproduction” [4].

On a final thought from the gray side, as a student of new media, I came to realize certain inequalities in opportunities, perception and navigation of today’s society. There is a bigger breach among individuals that have been surrounded by technology from childhood and understand its limits and possibilities oppositely to those just coming to know it, but this understanding of the gap may be also a fake understanding of our social reality, based on the illusion of the “creation of power” with this digital skills [3].

Being educated as a kid on computer skills, and software manipulation, even basic coding nowadays, comes with the promise of giving a range of abstract understanding and deconstruction and of course, a set of tools most likely required in our context. When facing the question of “skills” and experience there is a huge difference regarding the early accessibility to digital infrastructure; that doesn’t correspond to the individuals own interests and practices but to the social contexts and its limitations, giving some individuals advantages and putting others in specific action spheres that could be carried on in time, limiting their access to digital infrastructures out of fear, embarrassment, or just being uncomfortable to face something so familiar “so late”, under the eye of the capitalist society that kept them to the margin in the first place.

There are some cases, where the question is raised, whether this division is made by the capitalist itself and if everyone does, really, need these infrastructures to be part of this global system [5], but as long as the world is functioning on certain parameters there is no doubt that it should be a right for everyone to have the same access and understanding of how things are developing, and to be up to the individual to decide whether or not to be part of it, but in terms of voluntary action not in terms of lack of information, illiteracy or inaccessibility the same applies for government policies on digitalizing identities if its not possible for everyone it shouldn’t restrict and affect those who cannot be part of it.

References:

1. Governing ID: Principles for Evaluation. Bhandari, V. Trikanad, S. Since, A. 2020. A project of the Centre for Internet and Society, India Supported by Omidyar Network

2.Urban Form in the Helsinkiand Stockholm City RegionsDevelopment of Pedestrian, Public Transport and Car Zones. Söderström, P. Schulman, H. Ristimäki, M. 2015. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/33735222.pdf

3. Cultural Techniques of Cognitive Capitalism: Metaprograming and the Labor of Code in Cultural Studies Review. Parikka, J. 2014, University of South Hampton. pp 30 – 52

4. Amazon Is Forcing Its Warehouse Workers Into Brutal ‘Megacycle’ Shifts. Kaori Gurley, L. 2021 https://www.vice.com/en/article/y3gk3w/amazon-is-forcing-its-warehouse-workers-into-brutal-megacycle-shifts

5. Water, Energy, Access: Materializing the Internet in Rural Zambia, in Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures,Parks, L. Starosielski, N. 2015 Urbana, Chicago And Springfield: University Of Illinois Press. pp 115-136.

Agbogbloscene

The ever-increasing amount of electronic waste is a major global problem. Based on international studies, it has been calculated that a total of about 5,000 tonnes of electronic waste would leave Finland for developing countries each year, i.e almost a kilo per capita. The amount corresponds to less than five percent of the electronic waste generated annually in Finland. (1) The ‘recycling’ of e-waste in developing countries is much cheaper. The largest recipients of e-waste in Africa are Ghana and Nigeria, in Asia China, India and Pakistan. (2) It is estimated that more than half of the world’s electronic waste passes through official channels to developing countries, where only precious metals are collected from equipment, regardless of the health of workers. (3)

The interest of mining companies is based on the fact that recycling metals is cheaper than digging from the ground./(4)

It is not always so easy to separate used equipment from scrap. Many devices considered waste in Finland still get a new life in the hands of a West African repairman. Along with Nigeria, Ghana is Africa’s largest recipient of European used electronics. (1)

Ghana’s economy has grown rapidly, but living standards are still so low that there is a huge demand for used televisions and computers in homes, offices and internet cafes. Computers and other equipment are also repaired in small workshops.

Cows with open wounds graze on the site

The Agbogbloshie Scrap Yard is located a stone’s throw from the center of Accra, the capital of West African Ghana. There are several similar waste treatment sites on the outskirts of the city, but Agbogbloshie is Ghana’s largest and most researched – and has received the most negative publicity. “Sometimes we inhale toxic gases, and that filth accumulates in the body. But this work is the only way for us to survive, ”says scrap sorter Baba Adi. No one seems to have a respiratory protection. In Agbogbloshie and similar waste treatment areas, Finnish equipment will almost certainly also be disposed of. This is despite the fact that the export of electronic waste from Finland to developing countries is prohibited. Many working in the area are poor people who have moved from northern Ghana to the capital.

Adjoa, nine, sells small water bags to the workers. They drink it and use it to extinguish fires

They are attracted there by big earners. Sorters like Baba Ad can earn between € 150 and € 250 a month, about four times the Ghanaian minimum wage. The electronics waste business in Ghana generates an estimated € 200 million a year and directly or indirectly supports 200,000 people.

Cough and chest pain are common problems in Agbogbloshie. High levels of heavy metals such as lead and iron have been found in workers ’blood and urine samples. They end up in the body from air, water and food purchased from the waste area.

Kwabena Labobe, 10, plays on the site. His parents are not able to send him to school and forbid him to burn e-waste

Heavy metals are especially dangerous for toddlers living in the surrounding slums, who play in the scrap yard. Heavy metals end up in babies through breast milk. High levels of heavy metals have been linked in studies to nervous system damage in children and fetuses. There is no use for worthless parts of electronic waste. They are being dumped in informal landfills in Ghana. (1)

In Finland, the value minerals of equipment are collected mainly in industrial plants. Shipping goods to China is cheaper than a truck ride from Jyväskylä to Helsinki. According to one study, it is 13 times cheaper to separate gold, aluminum and other precious metals from electronic waste in China than to dig minerals underground. (1)

Most of the environmental impact of a smartphone, for example, comes from production. Digging metals and making components, or mobile phone parts, requires a lot of energy. (4) Even if you think of a basic cell phone or laptop, they may contain about 30 different metals. These metals come from all over the world. After the metals have been excavated, they go to a smelter or refinery, they may be made into various chemicals, then they go to a component plant and from there to an assembly plant where the equipment is assembled. There may be a real number of factories and operators before the metal ends up in the finished device and from there to the consumer. This is perhaps the main reason why it is really difficult to know where all the particles come from and under what conditions they are made.There can be dozens, hundreds or, for example, Samsung has 2,500 suppliers. (5)

According to a new study, if Europeans used their mobile phones a year longer than now, it would save two million tonnes of emissions, or about a million cars emissions, a year. The average lifespan of mobile phones in Europe is three years.

In the United States, 400 million electronic devices are rejected each year, an estimated 2/3 of which are operational. (5)

Europe generated 15.6 kilograms of electronic waste per capita. In Africa, the corresponding figure was only 1.7 pounds per capita. (6) And yet, more Africans have access to mobile phones than to clean drinking water. (7)

A total of 50 million tonnes of electronic waste is generated worldwide each year, of which only 20% is recycled. (5)

References:

(1) //https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-10472211

(2) /https://www.kansanuutiset.fi/artikkeli/3093042-eurooppalaisen-elektroniikkajatteen-paatepysakki-on-ghanassa

(3) / https://www.kuusakoski.com/fi/finland/yritys/yritys/uutiset/2019/elektroniikkaromu-vaarissa-kasissa-on-tietoturvariski/

(4) https://www.fingo.fi/ajankohtaista/uutiset/suomi-vie-elektroniikkajatetta-kehitysmaihin

(5) / https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-11141662

(6) YK:n yliopiston (UNU) raportti [vuodelta 2016] / https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-9296700

(7) THEORY BEYOND THE CODES Dust and Exhaustion The Labor of Media Materialism Jussi Parikka

Photos:

- https://news.itu.int/ewaste-growing-challenge/

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/gallery/2014/feb/27/agbogbloshie-worlds-largest-e-waste-dump-in-pictures / Cows with open wounds graze on the site

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/gallery/2014/feb/27/agbogbloshie-worlds-largest-e-waste-dump-in-pictures /Adjoa, nine, sells small water bags to the workers. They drink it and use it to extinguish fires.

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/gallery/2014/feb/27/agbogbloshie-worlds-largest-e-waste-dump-in-pictures / Kwabena Labobe, 10, plays on the site. His parents are not able to send him to school and forbid him to burn e-waste

- https://venturebeat.com/2017/06/13/5-billion-people-now-have-a-mobile-phone-connection-according-to-gsma-data/ Image Credit: Maxx-Studio

i(Don’t)*Fixit

Glossy black-boxed

Only once things fail, then we start thinking about their complexity and become aware of how much the tech objects that surround you are glossy black boxes, designed to appear simple and hide the enormous system that lies behind the object and stays far from our eyes. [1]

The whole world of media wants us to see its LED-luminescent and metal-polished side, but it is obscure in every other direction: the management of data signals arriving at our devices is a secreted activity; the production of the hardware is a story never told by the very firms, but only by journalists fighting for human and environmental causes; electronic waste is more of a taboo that both the big tech companies and the developed society do not want to deal with.

However. as Jussi Parikka argues, all these activities are not theoretical, but material [2]: data centers, data cables, coltan mines causing natural depletion in Central Africa, tech industries based on labor exploitation in China, e-waste landfills, and processing plants in Eastern Europe [3], they are all physical realities that shape entires societies. Taking all this dirt into account and using this as perspective, privilege is the possibility of looking at the result, but not the process.

Will to repair

If the single contemporary citizen has long-lived an imbalanced relation of power with companies, about their production methods and ethics, that could only be won through political pressure, he or she has always been able to take a little revenge through maintenance and mending. However, during the last twenty years, this has been made impossible or inconvenient by tech companies.

The activity of repairing has always been an important task throughout the history of humanity: resources have always been limited and the process of mending could be learned. In the last decades, we, the western privileged who have not seen the natural damages and the human exploitation, have been living in the illusion that resources were illimited and overall cheap, and we never learned how to repair our smartphones, computers, or whatsoever.

This has not happened for pure idleness, but a series of reasons [4]:

- Companies do not provide customers with software or adequate information for maintenance or repairing. If people start autonomously to deliver self-taught technical information, companies usually try to oppose, like Apple with iFixit. [5]

- Often companies do not sell the components either to companies or to non-official repair centers.

- Official repair centers are often so expensive that it is more convenient to buy the new version of the product.

Furthermore, if the life-guaranteed product would give a proper reason for the mending, programmed obsolescence conveys a renunciative attitude. In the era of e-waste, nobody would repair something that is made to break.

Right to repair

However, times are changing. People are now meeting in repair cafés [6]: there is awareness around these themes and organizations like The Repair Association (TRA) have been fighting for the electronics right to repair, obtaining some successes [7], even though big-techs try to remain black-boxed since people could hurt themselves while repairing their smartphones or hacker could have easier access to key information. [8] Of course, both of these argumentations have been found inconsistent, a façade for economic interests that is not working so well anymore. Indeed, knowledge is a form of power and, since tech firms have become important actors within the geopolitical system, the democratic citizen must ask for his right of knowledge, in order to be able to work out alternatives from the bottom.

–

Notes:

[1] Bruno Latour, Where Are the Missing Masses? The Sociology of a Few Mundane Artifacts, in Shaping Technology-Building Society. Studies in Sociotechnical Change, Wiebe Bijker and John Law, MIT Press (1992)

[2] Jussi Parikka, Dust and Exhaustion: The Labor of Media Materialism, Arthur and Marilouise Kroker (2013)

[3] Bulgaria Opens Largest WEEE Recycling Factory in Eastern Europe, Ask-eu.com (12th July 2010)

[4] Karen Turner, Apple wants to kill a bill that could make it easier for you to fix your iPhone, The Washington Post (17th June 2016)

[5] Kyle Wiens, iFixit App Pulled from Apple’s App Store, iFixit (29th September 2015)

[6] Sally McGrane, An Effort to Bury a Throwaway Culture One Repair at a Time, The New York Times (8th May 2012)

[7] Jason Koebler, Internal Documents Show Apple Is Capable of Implementing Right to Repair Legislation, Vice (28th March 2019)

[8] Jason Koebler, Apple Is Telling Lawmakers People Will Hurt Themselves if They Try to Fix iPhones, Vice (30th April 2019)

The Globalization of the Landscape

When companies sell us the cloud, it seems that they are talking about something magical and fantastic. Its imagery is futuristic looking, filled with shiny lights, and coming from a science-fiction movie. However, we are not concerned about what the cloud is. They are black-boxed and top-secret places, where all our information takes live.

We have seen attempts from the companies to make those spaces more transparent. They open the doors to the cameras and display all the machines. Yet, this hypervisibility of the infrastructure and this pure image that they give of the cloud allows them to keep the people naive.

The truth is that the cloud relies on data-centers that stock all that information that we generate every day. One of its effects is the need for infrastructure around the planet. These buildings are environments designed from humans to robots, and for that reason, their design is a copy-paste around the world. Data-centers are structures designed for machines, which means that no human is working in that environment, so there is no need to follow cultural necessities.

Images from data centers around the globe.

In the same manner during industrialization, the landscape was also affected by the construction of new buildings. Hilla and Bernd Becher, two german photographers, recorded these changes in the landscape from the late 1950s [1]. In their work, we can see collections of images depicting industrial buildings. Even if the buildings have very similar shapes because they have the same finality, there are subtle differences probably because of the construction methods and the cultural necessities from each place.

Pictures from Hilla and Bernd Becher’s work.

In the future, we will need more infrastructure to support all the data that we generate. Jennifer Holt and Patrick Vonderau write about one of the upcoming “technological dramas” that the technology in data storage is not as developed as the amount of information to store [2]. In conclusion, the landscape is going to be even more exploited in the future, overcrowded with the same buildings all over the surface.

References:

[1] Biro, M. (2012). From analog to digital photography: Bernd and Hilla Becher and Andreas Gursky. History of Photography.

[2] Holt, J. and Vonderau, P. Where the Internet Lives. Data centers as cloud infrastructure. Signal Traffic.

~ Alicia Romero

The Truth behind Pixels

Loop

At first glance, the development of the present media infrastructure, made by an articulated system of data centers, routers, cloud off-ramps, cables, satellites, and so on, seems unstoppable. Nicole Starosielski argues that we are in a feedback loop wherein data cables can be considered resources for audiovisual media and the very media are projected as resources for cables, allowing “the speculative development of large-scale infrastructural projects in the absence of any actual circulation.” [1]

Although media history is often characterized as a progression toward greater definition, fidelity, and truthfulness, is humanity going to rely more and more on those data-expensive media-rich contents?

Compression

Contemporary art, indeed, has already a long story of experimentations with a certain aesthetic of compression, described by Jonathan Sterne describes as a form of “proper management of content for the transmission lines” through the reduction of signal size for fitting in the media infrastructure. [2] As Hito Steyerls explains, the “poor image” is the copy made for movement: the more it accelerates, the more it deteriorates. [3]

Valentina Tanni explains that since xerox art to glitch art “pixels, primary elements of the computerized image, have been exhibited and exalted, […] low-definition is taken as one of the multiple possibilities of the image.” [4]

Simonetta Fadda argues that we have given to the HD image the task of replacing the reality that it reproduces, though this process inevitably “sanitize and sweeten” the contradictions of the very reality. [5] Consequently, lo-fi is a political choice that wants to ignore mainstream aesthetic and copyright culture, transforming quality into accessibility. [3]

Fidelity

As also Tanni points out, smartphones and webcams, far exceeding professional equipment, combined with lack of graphic education, generate a visual landscape where lo-fi images are the most frequent and authentic occurrence. Indeed, while looking at a “poor” image we would not doubt of manipulation, since, if it was, it would have been evident. On the contrary, a high-quality image is black-boxed: it does not reveal how far it has been manipulated.

While high-quality images are better at immersing us into a realistic representation of our visual existence, but keeping undisclosed their processual complexity, lo-fi images are democratically produced by the average digital citizen and “testify to the violent dislocation, transferrals, and displacement of images — their acceleration and circulation within the vicious cycles of audiovisual capitalism.” [3] Realism is not that realistic anymore.

Hyper-reality

Since this rising appreciation of the aesthetic of compression, the fact the humanity is heading directly towards a massive usage of media-rich contents can be put into discussion. Maybe the global mediatic infrastructure will not be overloaded and consequently overpowered (the usage makes the infrastructure!) just for a refusal to hyperreality.

After all, we sometimes prefer calling to video-calling, texting to audio, photographing to recording a video.

–

Notes:

[1] Nicole Starosielski, Fixed Flow, from Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski, Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures, University of Illinois Press (2015)

[2] Jonathan Sterne, MP3: The Meaning of a Format, Duke University Press (2012)

[3] Hito Steyerl, In Defense of Poor Image, E-Flux (9th December 2009)

[4] Valentina Tanni, Memestetica: Il Settembre Eterno dell’Arte, Nero (2020)

[5] Simonetta Fadda, Definizione Zero, Costa & Nolan (1999)

Tears of Joy

The forerunner of the writing can be considered numerous paintings and engravings that have survived from the Late Paleolithic period from roughly 35,000 to 15,000 years before the beginning of time. The birth of the actual writing took place in Sumer, ancient Mesopotamia, in what is now Iraq, about 3,200 years before the beginning of our era.(1)

In the 21st century, we are returning to the origins of written language, the world of symbols and signs. For the first time, in 2015, a picture was chosen as the word of the year in the Oxford Dictionary – a face laughing with tears in his eyes, called ´Tears of joy´. (2)

Our increasing use of smart devices and media has led to the simplification of language, the decline of literacy, and the replacement of traditional written language with partly different character and symbol systems, memes, and emojis. Iconic characters have begun to be used in writing alongside the old symbolic character set. They differ from iconic writing systems in that they have no sound value. (1) The popularity of audiobooks, the replacement of words by emojis and the increase in video call into question the importance of traditional literacy.

However, there is already talk of a post-text period, although it is difficult to think of replacing a scientific text, for example. Literacy will still be needed. Replacing long texts with a single meme image leads to an ambiguous visuality that requires different reading skills than a traditional text. Instead of literacy, we are talking about multi-literacy. At the same time, people’s literacy is declining.

-Bible as emojis

Do you recognize the verses below?

“Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind, and with all thy might.” The second is this: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself’. There is no commandment greater than these. ” The Double Commandment of Love, Mark. 12: 30

There are about half a million adults in Finland who do not have sufficient literacy skills to cope in today’s society (3) The decline in literacy leads to inequality in society. The danger is the polarization of society and the intensification of extremism.

The impact of political memes has been relatively little studied. Memes can be harmless entertainment that invigorates everyday life, but also a gateway to harmful extremism. Meme simplifies the worldview. Memes and humor are the most effective forms of influencing in social media. There is no direct evidence of planned political influence. However, that does not mean that it will not happen. In the future, trolling can be done with artificial intelligence and algorithms and can be controlled by states, among others. (4) The speed of communication and the lack of source criticism easily lead to the spread of belief information and the fragmentation of the field of knowledge. The content of search engines and the Internet is over-relied on, and at the same time search engine companies have infinite power over the dissemination of information. The governance of search engine companies is a huge political controversy.

On the other hand, the problem is the decline in human brain capacity globally. Professor Gerald Grabtree puts it this way: “I would even bet that if the average citizen from Athens now came to us thousands of years ago, he would be the smartest and most intellectually capable of our party. He would have a good memory, wide-ranging ideas and sharp perspectives on important things. ” The rationale for the hypothesis is that man no longer needs his intellectual abilities to survive in modern modern society. And when intelligence is no longer needed, the genes that support it begin to decay as a legacy for future generations. (5)

Evan Horowitz also writes in an article published by NBC: Humanity is becoming more stupid. That is not an estimate. That is a global fact. IQ results have begun to deteriorate in some of the leading countries, (2). One explanation for this, according to Horowitz, has been that food no longer receives as many nutrients due to global warming. The information society has also been blamed for the flood of information, which is seen as undermining people’s ability to concentrate. It can also undermine humanity’s ability to respond to massive problems such as climate change and the challenges posed by artificial intelligence. (6)

(1) Kuvakirjoituksen jälleensyntymä – tunneikonit kirjoitetussa puhekielisessä keskustelussa ^__^ / / Pro gradu -tutkielma Suomen kieli Turun yliopisto Toukokuu 2006, Ilmari Vauras / https://www.jammi.net/tunneikonit/ilmari_vauras_pro_gradu.pdf

(2) https://www.is.fi/digitoday/art-2000001037217.html

(3) Meemien tulkitseminenkin vaatii lukutaitoa – Mitä käy niille, jotka eivät opi lukemaan?/Salla Rajala, 27.9.2019

https://moreenimedia.uta.fi/2019/09/27/mita-kay-niille-jotka-eivat-opi-lukemaan/

(4) Viihdettä vai aivopesua? Meemit vaikuttavat ajatuksiisi, etkä välttämättä edes huomaa sitä

, 20.9.2019, https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-10941826

(5) https://www.iltalehti.fi/terveys/a/2012111316323790?fbclid=IwAR1dY8mmOTaSmcWCxnqsvjX5v7s0NpDAUjrX_Ab4ipB3rdzU33Oi34z4VQI

(6) Ihmiskunta muuttuu tyhmemmäksi. ”Se ei ole arvio”.

SIINA EKBERG | 23.05.2019 | 23:55- päivitetty 23.05.2019 | 19:10

/https://www.verkkouutiset.fi/ihmiset-tyhmenevat-ja-silla-voi-olla-kohtalokkaat-seuraukset/#6628a248

Thanks for the inspiration to Alicia Romero Fernandez

Pictures:

1. https://fi.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuolenp%C3%A4%C3%A4kirjoitus

2. https://www.is.fi/digitoday/art-2000001037217.html

3.https://www.wycliffe.fi/emojit/

-Bible as emojis

Do you recognize the verses below?

“Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind, and with all thy might.” The second is this: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself’. There is no commandment greater than these. ” The Double Commandment of Love, Mark. 12: 30

4. picture manipulation: Tuula Vehanen

Cable Innocence

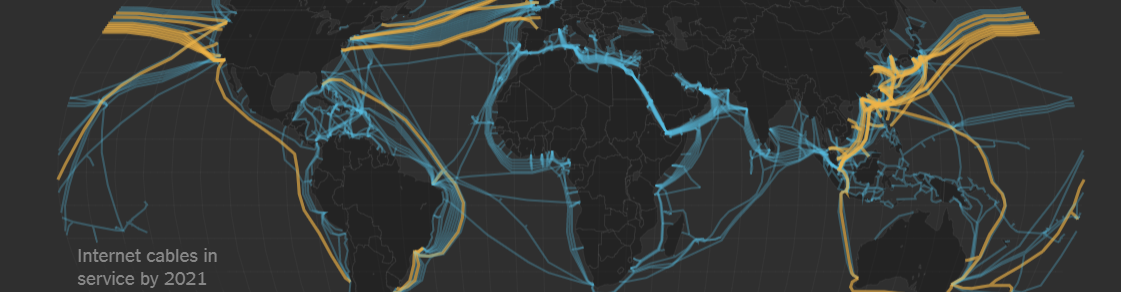

In 2020 the submarine cables take up a length of approximately 1.2 million kilometers [1] which is an impressive number, too large to comprehend and thus as unreal as the ceaseless wireless data connection itself. But the cables are physical, of course, and require not only manufacturing, but also installation and maintenance. And presumably – lots of money for lots of power in return. But for a commercial, artificial and physical entity spanning across oceans, cables seem to have gained more sympathy (or more sympathetic vocabulary) than I would have expected.

There is a history of submarine cables starting with telegraphy traffic in the 1850s, but these days submarine telecommunication cables are fiber optic cables that operate by shooting pulses of light through transparent fibers usually made of glass or plastics; cables laid under the seabed are wrapped in protective layers made of steel, copper, and polyethylene, and are equipped with repeaters that are additionally powered by a power cable [2]. When possible, these cables are buried under the seabed in the sand, but when impossible (or sometimes not legally required) they are laid on the seabed and covered up with concrete mattresses, rocks or cast-iron shells for protective reasons [2].

Invasive and alien as they are in the submarine environment, cables and cable laying seemingly does not have an alarming impact on the environment and underwater fauna. Related environmental impacts include underwater noise, heat dissipation, electromagnetic fields, contamination, and disturbance [2], but they are largely seen as minor, temporal, and transient. And strange as it seems, according to biologist Brian Bett, old and unused cables could even be abandoned in the ocean, as “there could be a carbon footprint assessment of the diesel fuel used to recover them”, and very often that is the case and cables, as well as repeaters, are left in the ground [3]. But this somehow seems to oversee the fact that fiber, metal, and plastics are still waste buried deep into the oceans, disrupting nature.

There is a reported incident of a humpback whale entangled in a data cable near the coast of Norway, which is rescued by the coastal guard in two days time after accidental spotting by a nature photographer [4], but for as much as we can see (and given the depth of the ocean – it’s not much) modern cables have also spared the large marine mammals. Rest aside the environmental impact of roaring data centers and power usage of ever-increasing multimedia content and data consumption, cables are starting to seem truly innocent.

And interestingly, as such, they are also depicted in the public discourse – vulnerable and in a need of defense. Cables as such are subject to various faults – accidental human activity and occasional earthquakes and underwater slides, but at this point, cables are laid across different routes and customers are rarely aware of disruptions, with main losses being for the telco industry [5]. In 1958 The International Cable Protection Committee was founded [6]; CNN depicts cables as being vulnerable, BBC asks Could Russian submarines cut off the Internet?, and various UK government officials seek attention for the insecure [7] cables and their defense [8]. The overall depiction in media also seems to follow the line of magnificent, but vulnerable network, without posing questions of ownership and thus, power relations.

Without a deep knowledge of the secretive cable industry and large tech companies, this discourse can seem alarming, inviting the public to hope for the protection of the cables, as if the cables were a part of our private selves. Fearing the Russians, fearing a communications cutout, fearing a disruption of our Internet-dependent private realities, fearing a moment in a dystopian future when all the cables crash and we are left out of reach. For the most part, the world has grown dependent on submarine data cables and companies planting, maintaining, and owning those cables, so a general public vouching for the cables (thus, vouching for the companies, no questions asked) seems like a logical if not fearful attitude, for the power is too enormous to challenge. And even one step further, if I may – public fear in itself is quite a resource.

Resources:

[1] Submarine Cable 101. URL: https://www2.telegeography.com/submarine-cable-faqs-frequently-asked-questions

[2] Institute of Applied Ecology. Impacts of submarine cables on the marine environment – A literature review. URL: http://www.naturathlon.eu/fileadmin/BfN/meeresundkuestenschutz/Dokumente/BfN_Literaturstudie_Effekte_marine_Kabel_2007-02_01.pdf

[3] Boztas, S. Buried at sea: the companies cashing in on abandoned cables, 14.12.2016. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2016/dec/14/ocean-pollution-cable-waste-technology-reuse-recycling-circular-economy-crs-holland

[4] Coghlan, A. Hacker, the humpback whale who got tangled in an internet cable, 16.11.2016. URL: https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg23231000-400-hacker-the-humpback-whale-who-got-tangled-in-an-internet-cable/

[5] Griffiths, J. The global internet is powered by vast undersea cables. But they’re vulnerable. 26.07.2019. URL: https://edition.cnn.com/2019/07/25/asia/internet-undersea-cables-intl-hnk/index.html

[6] About the ICPC. URL: https://www.iscpc.org/about-the-icpc/

[7] Sunak, R. Undersea Cables: Indispensable, insecure. 1.12.2017. URL: https://policyexchange.org.uk/publication/undersea-cables-indispensable-insecure/

[8] Barker, P. The Challenge of Defending Subsea Cables. 20.3.2018. URL: https://www.maritime-executive.com/editorials/the-challenge-of-defending-subsea-cables

No/humanness in the Immediate

We are becoming ever more impatient, and waiting which will always be part of any process [1], seems more like an inadequacy in the human code, there’s this old fixation with utility and efficiency which is slowly killing all that is organic within ourselves and surrounding us. From the days of industrialization, and the beginning of the engine era, our pace has constantly been stepping up affected by new technologies [1]. Being modern is being fast and productive, our wireless context allows and so many other times demands us to be in many different places at many different times, we are living the future, the same future that, as years ago, relies on the cultural obsession with immediateness and the well-developed infrastructure illiteracy.

Our cultural geography and temporality are ruled by capital systems, who, more than ever, are putting a value on time, we’ve come from having tangible benefits in reducing time on communication systems to making immediateness a final product itself. Another phenomenon is the overgrowing invisibility of infrastructures and with these a lack of understanding of who controls those services we rely so much on upon; by these means, we might live under the impression that investments to obtain better accessibility may be part of our nation’s interest in the common well and better social development but the reality is that nearly all, if not all, internet infrastructure belongs to private companies [2] and such investments have as final ends the creation of more need rather than providing solutions.

These private owners are in constant search of investors and expansion grounded on probabilities of data consumption [3], an interesting approach on this matter is to analyze the extent of services these private companies own and how they use user data for developing still unneeded infrastructure base on, the already capitalized, searches, screen time, and clicks, to name a few. It is no wonder that their main interest is to keep providing quick and borderless access to such services as they plan to expand and create more apps and services that will demand broader data access, creating an ever-accelerating cultural imaginary [4].

The idea of services beyond geography and borders may seem utopic but in practice, they come with rather problematic issues. The fact that most of these infrastructures rely on private entities who are not engaged in national matters such as, territory or natural resources affairs, or national privacy policies are some practical problems, but on a cultural imaginary scale, we have to understand the power we are giving to such entities, especially, in the social understanding of time and immediateness, and how these perceptions are being translated into other spheres such as education and culture.

As an effect, time is, more and more, being perceived as less useful on critical and investigating spaces because of the lack of practical utility [5] but especially because they are not at the same pace with the cultural imaginary pace that telecommunication infrastructures have created. While being obsessed with immediateness we are pushing ourselves towards a practical conception of reality, where our attention is shifting from being analytical and explorative to producing and consuming cyclicly at a fast speed. This phobia of waiting is affecting the way we understand information and also how it is being taught; nowadays education institutions rush students to get their degrees done quickly, courses cut studying hours by half, and there is a tendency for more self-studies. By assimilating the accelerating pace of infrastructures we are putting at risk capacities to generate ideas, instead of quickly searching for pre-solved answers.

Nowadays it is almost a revolutionary act not to follow what some app says and choose to be consciously slow on our way to our next meeting, or that inevitable metro trip, adding some non-efficient gap in our routine and it is even more revolutionary to go through one specific topic all over until words lack sense. We are expected to know things or search them immediately if not the case. Exploration and mistakes are permitted but there are limits and deadlines. Time is ticking constantly and on the other side of it, are the communication networks making it go even faster.

Knowledge isn’t immediate, isn’t invisible, these big entities are looking for blind and illiterate users, to keep on growing at an accelerated pace. We have to question what’s the limit of our unstable ethics and start visualizing the physicality and social effects of this unrestricted massive political private control before there’s only left generations of systematic consumers with no further soul or purpose.

Resources:

[1] Invisible and Instantaneous: Geographies of Media Infrastructure from Pneumatic Tubes to Fiber Optics. Farman, J. 2018. Geospatial Memory, 2 (1), pp.134-154.

[2] Submarine Cable Map. https://www.submarinecablemap.com/#/submarine-cable/sweden-estonia-ee-s-1

[3] “Fixed Flow: Undersea Cables as Media Infrastructure,” in Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures. Starosielski, N., Urbana, Chicago, And Springfield: University Of Illinois Press, 2015, 53-70.

[4] The Tech Giant’s Invisible Helpers. Ovide, S. 2020 https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/08/technology/internet-infrastructure.html

[5] In defense of the useless. Ordine N. 2016. https://www.cccb.org/en/multimedia/videos/nuccio-ordine/223112

Greening Google

In the mediatic sphere, there is a strong association between the imaginaries of digitization, electricity, and environmentalism. We do think that an electric car is “greener” than a diesel-fueled one. We do imagine smart cities fully digitized, electric, and merged with the natural ecosystem, like the projects by Studio Stefano Boeri [1]. However, there is a growing perception that this could be a big misunderstanding.

For example, in 2019 OVO Energy has calculated the carbon footprint of emails and asserted that in the United Kingdom “if every email user in the country were to send one less unnecessary email per day, that would reduce carbon emissions by 16,433 tonnes,” [2] and then gave a metaphor to “contain the messy reality of infrastructure” [3]: 81,152 flights from London to Madrid.

The unexpectedness of these data makes this question is then immediate: are we in front of a case of greenwashing operated by the media industry? Formerly known as “eco-pornography” thanks to former advertising executive Jerry Mander, “greenwashing” is a concept born in 1986 by biologist and environmental activist Jay Westerveld, but with still no univocal definition. Riccardo Torelli, Federica Balluchi, and Arianna Lazzini then agree to trace the vague borders of this practice calling it “a misleading communication practice concerning environmental issues.” [4]

According to Greenpeace reports examining the energy consumption of data centers and cloud infrastructures, “if the cloud were a country, it would have the fifth-largest electricity demand in the world,” mostly used for keeping “servers idling and ready in case of a surge in activity” [5]. And at the same time, various companies like Google, Facebook, or Apple send messages about their effort in the construction of more energy-efficient structures and green energy plants that partially cover the enormous energy demand.

However, while looking at this oxymoron, the wisest question is then to ask: can these companies do otherwise? What is the budget percentage spent by GAFAM in researching less consuming infrastructures? And by our governments? If we are judgemental about Google building hydroelectric plants, how should we behave with those who are not even doing this?

And provoking finally: can we accept to have a more mediocre cloud service for a greener planet?

–

Notes:

[1] Stefano Boeri, Tirana Riverside, Tirana, Albania (2020)

[2] Martin Armstrong, The Carbon Footprint of ‘Thank you’ Emails, Statista (2019) https://www.statista.com/chart/20189/the-carbon-footprint-of-thank-you-emails/#:~:text=The%20sending%20of%20one%20email,at%20on%20a%20national%20scale.

[3] Star and Lampland, Standards and Their Stories, 11.

[4] Riccardo Torelli, Federica Balluchi and Arianna Lazzini, Greenwashing and Environmental Communication: Effects on Stakeholders’ Perceptions, from Richard Welford, Business Strategy and the Environment (2020) https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/bse.2373

[5] Jennifer Holt and Patrick VonDerau, Where the Internet Lives: Data Centers as Cloud Infrastructure, from Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski, Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures, University of Illinois Press (2015)

Fe Simeoni

–

fesimeoni.it Ig

DIGITAL WASTESLAND

We come from mentioning the physicality of some infrastructures, they really on land, minerals, material resources to function, the same applies to our data, software access information, contacts, events, preset alarms, passwords, overall everything we want to keep somewhere within our multi-dimensional and for that matter multi-temporal reach.

The cloud provides a solution to storage and accessibility not to just one type of data but to overall our entire functionality, with connectivity we gain the possibility to access our information from everywhere, we also gain unawareness and inability to filter what to hold on to and what to dispose of, we lost track of what we’ve kept dragging and even worst what we’ve been keeping somewhere around the data landscape – which is in a grey zone of the private and public domain [1].

With the lack of awareness of the physicality of data as compared to the weight of ten books or the space a thousand photos would take of our intimate spaces, it is hard to understand data accumulation as an issue, especially since digitalization provided certain relief from waste and space overload. How much are we storing and for what purposes? And where does this data goes? As before mention digitalization may have solved some waste and storage issues but it’s not ethereal it is as physical as it gets, as any other infrastructure, and in this one, in particular, there’s an accelerated growing directly link with our production and consumption of data. So then again I raise the question, is it really everything essential?

We are directly accountable for the creation of exponential data centers, massive physical infrastructures with over the top energy consumption whose sole purpose is to store data that could be otherwise kept somewhere unidimensional with limited access rather than the cloud or moreover don’t exist at all, it’s important to take into account also data accumulated into what is known as Big Data. Companies profit from our detachment of data physicality and keep on magnifying such alienation by offering more abstract space in the cloud to storage a lifetime of pure digital waste. [2]

Therefore, we are part of a capital cycle where we keep on expanding limits and accepting terms and conditions while paying monthly fees for this “space” with no understanding of what this implies or where the actual space is located, even worst, who does it really belong to [3]- such type of contracts is unthinkable outside this sphere. They keep on pushing us to fill those new limits with false pretenses of “the unlimited” but there is a limit to our resources and to how many data centers our lands can hold before they turn natural landscapes into ghost-cities with more electricity consumption of those of proper habited countries, this matters especially having in consideration that there are still cities that don’t have this resource at all, is it then worth thinking of such investments while others still live on total darkness? [3]

Some of us as individuals try our best to reduce our footprint by buying local, eating vegan, even buying second-handed but then again we are not aware of the implications of our lack of memory, our inability to recollect phone numbers, addresses, authors, or even appointments, not to mention the countless pictures and videos just to pick one for the day’s post. At what cost, are we accumulating there in the “ethereal” causing the exhaustion of resources, populating the world with shallow electrified buildings.