In this post, I’ll summarize some techniques that have worked for me when working on projects where I don’t have immediate outside pressure or given structure. This is a snapshot of some techniques I find helpful at the moment. I don’t expect these techniques to work for everyone.

Balanced scorecard

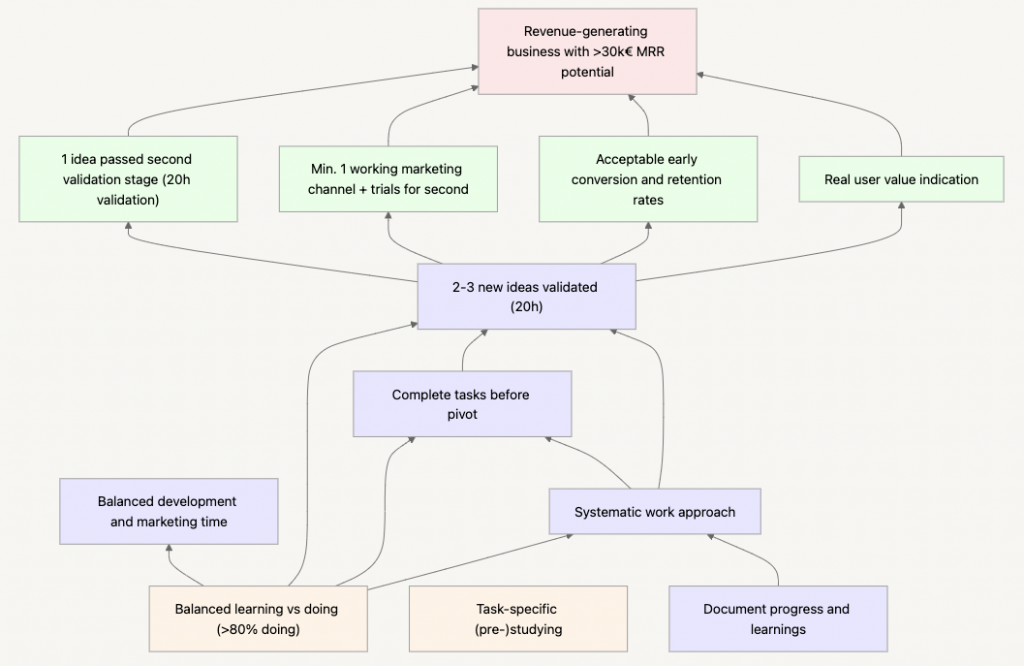

I learned about the Balanced scorecard in the Management Accounting II course. I found the bottom-up and concrete-tasks-to-targets approach interesting.

I also connected the idea to a convincing way of presenting that I had observed at a previous workplace, where a colleague leading a new consulting unit presented their strategy using a similar framework. Their presentation consisted of three main points:

- What are the ultimate goals for a strategy period (e.g., a year)?

- What are the concrete tasks that we’re doing to achieve these goals?

- Are we on track with the concrete tasks?

I’ve found this idea helpful when trying to combine the big picture with day-to-day tasks. A revelation was that we can’t be accountable for the ultimate goals because of the inherent uncertainties. Still, we can be accountable for the concrete tasks that might lead to the goals. A balanced scorecard actually has four layers, but the idea can be boiled down to just two: goals and tasks that help achieve them.

For a hands-on-oriented, pragmatic person, creating a balanced scorecard-like plan might initially feel stupid. How can I know that the concrete tasks actually lead to the goals? Why should months of work be guided by a plan created in an afternoon with what is ultimately just guesswork without any real data about causalities or the best course of action? Isn’t this just another worthless business jargon-filled hand-wavy consultant thing? However, what is the alternative? Without this kind of plan, I used to have no plan or, at most, just a vague idea in my head. Writing things down and thinking about the possible causal connections helps concretize and improve the vague mental plan. Sure, there is no certainty that the plan will work, but a perfect plan does not exist with the uncertainties involved. The key is to start with the end result and ask yourself: what would someone likely have done day-to-day to achieve similar goals?

Here is a concrete example of my balanced scorecard-like plan for about a three-month period. It contains things that might not make sense since they relate to my situation and things I noticed I struggled with before creating the plan.

Pomodoro

Pomodoro is Italian for tomato. The creator of the technique used a tomato-shaped kitchen timer to track his work intervals.

In all simplicity, the technique consists of working in 25-minute, non-interrupted, intervals. The working interval can, of course, be longer or shorter, but the official pomodoro is 25 minutes, with set breaks.

Suppose I find myself trying to avoid work by opening a new (not work-related) tab in the browser, checking my phone, or something similar. In that case, I find it helpful to decide that I’ll work for the next 25 minutes no matter what.

Before the Pomodoro period, I decide on a concrete task I need to work on. 25 minutes is a short enough period that it doesn’t feel overwhelming.

During this period, I don’t have to get anything done; I don’t have to stay focused. I’m just not allowed to do anything else. Often, I end up working for longer than 25 minutes. If I can’t concentrate and get nothing done, at least I know I tried. However, it has never happened that I wouldn’t have achieved anything during a Pomodoro period.

Hour tracking

Hour tracking helps with accountability and can reveal the actual time spent on tasks versus the time you think (or wish) you spend on them.

There’s a balance to strike: you need to spend enough time on tasks regardless of how productive you feel, yet ultimately it’s the output, not the input hours, that matters. Still, there is a correlation between the two.

My target is at least 25 quality hours of work per week, which might sound low. My general guideline is to push things forward every day, even on weekends, unless I have something special planned. I only track real, focused hours, excluding breaks.

I don’t need to track my time for naturally engaging tasks like implementing software. For tasks I don’t like doing, like marketing, focusing on time spent helps me ensure I’m making progress.

For hour tracking, I use a simple Google Sheets document.

I find similarities between being self-employed and exercising. With both, most people know what needs to be done – the challenge is consistently executing day-to-day tasks over a long period.

I’ve been able to maintain a consistent routine for years. While I’d like to credit my self-discipline, I suspect I’m simply drawn to routines and structure.

It’s less about iron discipline and more about discovering the mental tricks that work for your particular mindset and situation. In fact, I believe it’s impossible to rely simply on self-discipline. Sooner or later, it will fail. Learning the tricks that work with your monkey brain, and forming habits in a way that doesn’t strain the mental discipline muscle too much is the only way to success. In my case, although I’m happy about making constant progress, I’m constantly not happy with my rate of progress (e.g., the 25-hour weeks of productivity). I’m trying to learn the tricks needed to increase my output.