By Hanna-Máret Outakoski, Sámi allaskuvla/Sámi University of Applied Sciences, Oahpaheaddjeoahpuid goahti/Department of Sámi teacher education, Norga/Norway.

Cindy Kohtala, Umeå University, Umeå Institute of Design, Sweden

In our first workshop, called Making Territories, we were hosted by Sámi allaskuvla, Sámi University of Applied Science in Kautokeino, Norway, see Photo 1. Sámi allaskuvla is located at the heart of Guovdageaidnu/Kautokeino municipality in Finnmark, Norway. This is a territory of reindeer herding tradition that is still following the seasonal movements of the reindeer herd. This is also where the Sámi language is the main medium of communication in the worklife as well as in the private life of the people. Traditional knowledge is still a part of the everyday life of people, as is making and crafting.

As our meeting took place in April 2025, the reindeer herders of the area were moving their reindeer to summer grazing lands. The spring move was accompanied by strange weather that had continued from the autumn, keeping the hard crusted snow on the ground also up on the mountaintops. The unpredictability of weather and snow conditions, and threats to the sustainable future of the core Sámi livelihoods, were trending as a subject in many academic talks and as a main topic of the coffee break discussions during that spring at Sámi allaskuvla. In many ways our first network meeting on making knowledge on sustainable transformations (MAST) seemed to be at the right place at the right time.

The workshop

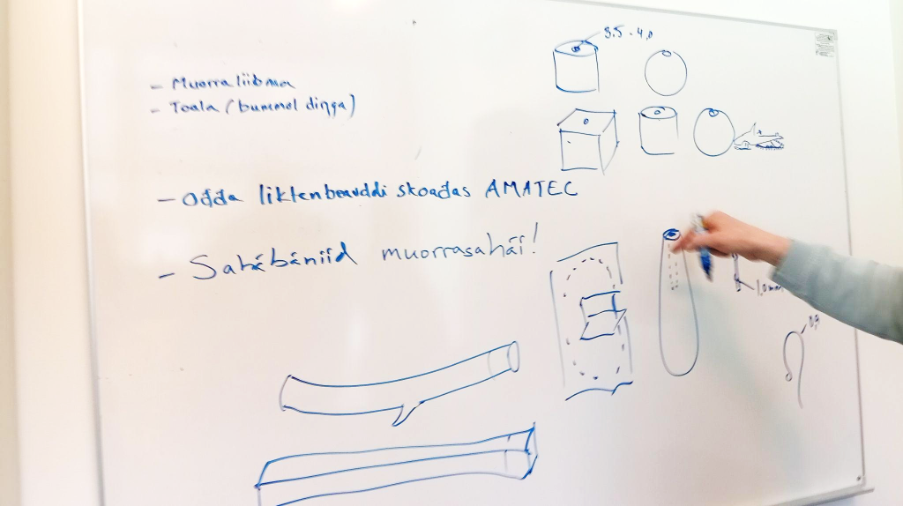

The three day workshop was structured to encompass short introductory and informative lectures; working hands-on with reindeer-bone porcelain, reindeer antler, and wood, under the guidance of experts; and ongoing discussions while making and presenting, see Photos 2 and 3. We were fully focused on learning about – through talking and doing – duodji and the knowledge and experience that duodji embeds and embodies. (Further reading: Duodji as a Starting Point for Artistic Practice)

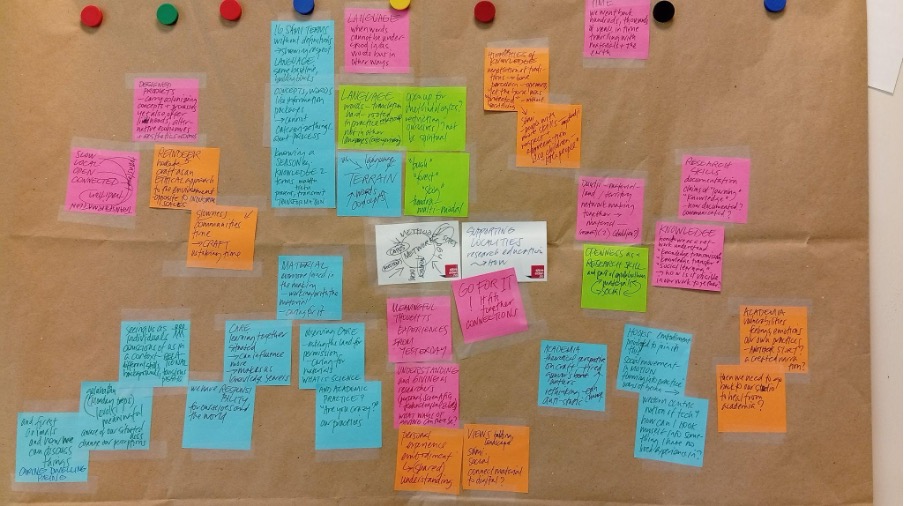

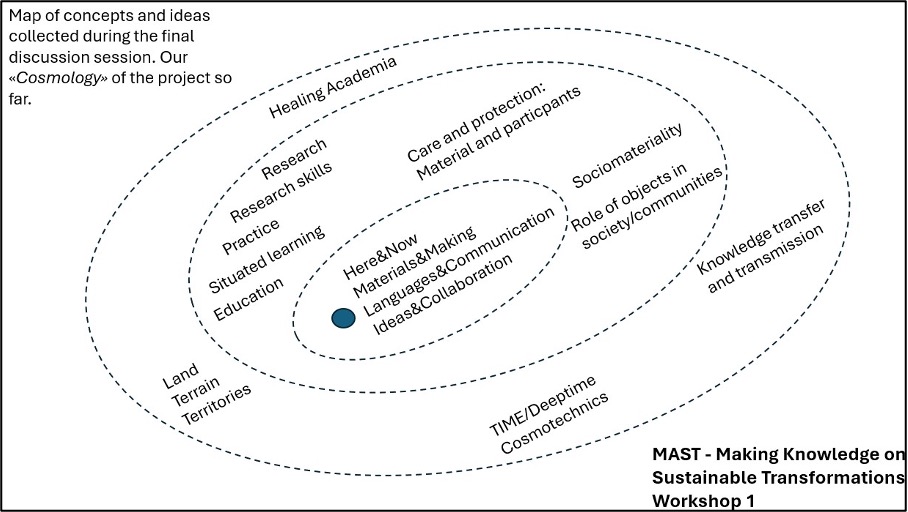

We then drew together our learnings and experiences by putting forward first reflections in one round and then deepening the insights and commenting on others’ in a second round. The discussion wove together the interface of language, embodied experiences of making, and knowledges of landscapes, conditions, soil, environments, histories and materials. We led ourselves through a rich story of the future of things, the role of objects in society, and a more profound understanding of “socio-materiality”.

Sites and materials

While the term ‘care’ is vulnerable to overuse and superficial understanding in today’s academic environments, we came to know and feel how care for sites, soil, land and localities manifests in care for materials and things. In highly urban and hypercapitalist, consumerist contexts, such ways to care have been forgotten or have been made invisible and undervalued. In many cultures there may even no longer be words that carry such practices in language as a technology.

Let’s consider the example of luonddu oassi: Professor Gunvor Guttorn explained this concept by telling us a story of her father, who had taught her about antlers. It was important to leave antlers that had already fallen on the ground to stay on the ground if they had been there for some time. “Nature’s share” means that one should give back to nature what is meant to be given back. It is then up to the person to decide and when this is appropriate and when it is not needed.

We also worked with reindeer bone porcelain, and ceramist researcher Mirva Kosonen, a master’s student at Aalto University, coached us on how to care for the material and how to make forms with it that respects its nature, see Photo 4. Through her lecture, watching her work and having her guide us in understanding the material, we had flickers of memory from our ancestors having lived with mountains and stone turned to dust and soil and clay, over thousands of years. In a way, some of us felt that working with this novel material (china of reindeer bone rather than cow bone) connected us more deeply with the profundity of nature and the earth, human endeavour, and even further back to the creation of the continents. Deep Time.

Language as an interface

Language and terminology were very much at the centre of our meeting that brought together researchers and artists from four Nordic countries. Many of us had roots in cultures and places outside the Nordics. The common language for communication during the network meeting was English. However, the conversations between individuals showed a much more versatile take on communication as different languages were accompanied by embodied non-verbal communication, pictures and drawn examples, non-verbal hands-on instructions on how to work on certain materials, emotional signals, and much more.

During our workshop, 16 central Northern Sámi terms or concepts were mentioned (some of which are mentioned also in this text). Most of the time, the Sámi concepts were not accompanied by a translation or explanation, but the Sámi participants used them naturally as parts of speech when speaking about the Sámi worldviews, materials, values, nature, arts and crafts. Presentations and talks given by the Sámi representatives and leaders of the Sámi crafting sessions also emphasized that relations and relationality are at the centre of Sámi ontologies and epistemologies. This view obliges the researcher, or the artist, to consider responsibilities toward the lands, the materials, and the powers in nature, and to respect the ways procedural and process-oriented knowledge is generated, stored, and mediated. During our final sharing session, one of the participants’ wishes was to get a deeper understanding of the central Sámi concepts to be better prepared to meet the expectations and needs of the future research collaborations with the Sámi academic and non-academic communities.

A Safe Space for discussions

As such space was created, we were able to understand certain Sámi terms as concepts without verbal definitions. We were able to come to this understanding through the discussions and making/creating together. In the meetings, we were open to sensitive questions at the same time as we were committed to caring for each other as researchers, practitioners, craft-makers (duojár), academics, and teachers. In many of the conversations, this kind of opportunity to meet and discuss matters from different perspectives was seen as an example of methods that can be used for healing academia. We also agreed on having several views on what the need for healing was, depending on the disciplines and the many research perspectives that the group members represented, as we come from different research contexts.

During our first network meeting, the goal for the meeting was to reach a state of successful exchange of ideas. A Sámi term, that was introduced early on during the network meeting, was “gulahallan”. This word has morphological parts that refer to hearing and making someone hear, a kind of reciprocal relationship and a complexity that tells us that the meaning of the word cannot be so simple. Gulahallan is also mentioned as the first Code of Ethical Conduct in the freshly published Ethical Guidelines for Research Involving the Sámi People in Finland (nbnfioulu-202405294076.pdf). In that publication gulahallan is explained as reciprocal communication and engagement. Here, we could describe gulahallan as being about having conversations and discussions, keeping in touch, with the goal of sharing insights as well as being open to other people’s understandings and views. This kind of meaning making process can also be extended beyond human-to-human conversations including, for example, the processes of reading and understanding one’s environment. English words such as communication, dialogue, mutual comprehension, and negotiation of meaning indicate some of the joined meanings of gulahallan, although they seldom extend to situations beyond human-to-human interactions. Successful gulahallan means that there has been a state or process of coming into a mutual understanding of things, even if it entails that some views are recognized and accepted as being opposite to each other. A non-successful gulahallan can be any kind of communication where, for example, the conversation partners either do not manage or want to create a mutual understanding of things, or they are not in tune with the goal of gulahallan in the first place, the direction of the communication is a one-way route, or there are other, perhaps external, reasons why the gulahallan does not succeed.

Time and temporality

This was another central theme that became evident, as our discussions led us to a further illustration of what we saw as the ‘cosmology’ of our overall project. We saw ourselves in a timespace where we are “here and now”, yet connected through hundreds, even thousands of years in the past, through practices and materials, to visions of the futures we wish to see. This was possible especially through working with reindeer bone porcelain and antlers and the connection of the human, community, livelihood, animal and soil, as we indicated earlier. Gunvor in turn guided us into another time dimension where materials are collected and their interrelations cared for, over long periods of time. (Want to read more about Deep Time and temporality? See e.g. The Deep Time Walk – How Effective Is It? and Deep history and deep listening: Indigenous knowledges and the narration of deep pasts.)

At the end of the workshop we collected and synthesized our ideas and insights into a “research map”, see Photo 5, which became something of a “Cosmology” of the first meeting, see Figure 1.

Final thoughts

Through our work, we address research, education and practice and the importance of care ethics, which informs the research skills we wish to foster throughout the project. Through this we see making practices as part of a healing academia by which we know better how to care for land, materials and other relations.

Interestingly, given our attention to language, we did not use the word “territory” very often, even if the title of the workshop was “Making Territories”. Instead we referred to terrain, land, landscape and other relational terms that do not carry the baggage of a damaging colonial history wrought by the global North. In fact, this is a compelling point to address in future in our network, in North-South dialogue. In Latin America, territorio has been a term connected to resistance and protecting land and community from oppression (Further reading: Space, Power, and Locality: the Contemporary Use of Territorio in Latin American Geography).

If we are losing language, if words lose their meaning and techniques become tools of extraction rather than enrichment for localities, how can we regain what we need to survive and thrive in sustainability transformations? Perhaps we can make small steps together and learn in knowing-through-making.