This is bit of a side path but that doesn’t matter. In my experience, while studying something one often is interested and curious about subjects adjacent to the actual target of the research. In my case this side step was into the world of theatre. This happened when I dug into the doctoral thesis of David Lu!! (remember him from the previous post?) entitled Contextualized Robot Navigation. The main interest in the thesis is studying the way robots navigate when encountering humans in a manner that allows both robots and humans to pass each other efficiently. This requires the robot to “fake” social cues and gestures with its actions. The robot’s gaze (where is pointing head toward) has been highlighted as one of the most important aspects of human robot interaction.

In his thesis, Lu explored theatre acting as a way of understanding how robots should act in order to adjust to socially acceptable behaviour. Acting is humans trying to portray how humans react to events and specific situations. Similarly, the point is to study how robots could act in a way that humans do. That’s why acting techniques can be quite beneficial when trying to teach robots how to act like humans.

However, if the robot is coded a set of actions that it performs in a timed sequence, a human actor also becomes a robot because they would not be reacting but merely timing their actions as well, which is not truly reactive and leads to hesitation and unsure performance.

David Lu!! discusses two types of acting: Responsive acting and Method acting. In Response acting one does not have any motive to achieve a goal or an objective. In responsive acting one only reacts to surroundings, which requires heightened senses and disregarding motivations. This state is also referred to as “empty head” in improv theatre, meaning that you do not thinking about anything, anything at all, just react to what is happening.

“The Method” school of acting is something else entirely. In Method acting, the actor uses a deep emotional experience from their past that they try to relieve to authentically convey emotion on stage to achieve their goal. The actors are pursuing a goal such as “I want to convince this person to give me money” or “I want her to fall in love with me”. This is impossible for robots, since they do not have feelings, however, they can have goals.

How does any of this relate to energy efficient mobile robots?

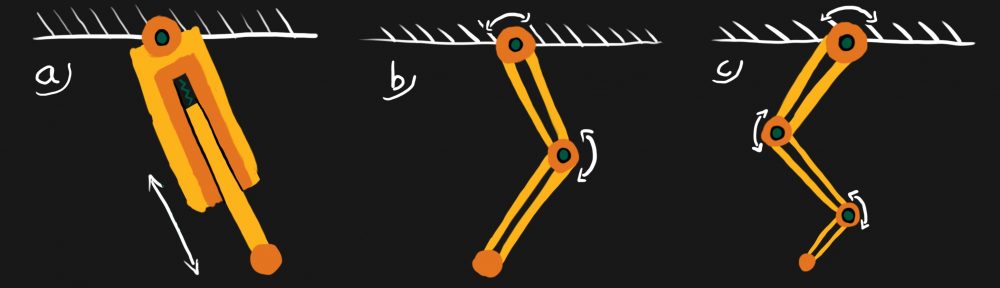

Well, it does. Typically, a navigation algorithm of your robot has a single goal (this is called single constraint navigation) to find an efficient collision-free path. Such algorithms are insufficient when there are humans in the environment who do not know how to act when encountering a robot, who does not respect social norms such as aligning to the right side of the hallway already when seeing a human from a far or making eye contact.

Standard navigation vs. social navigation by David Lu!!. In social navigation, the robot is aligning to the right already when it notices a human from afar and uses it’s gaze to point where it is headed. This results with a more smooth passing of the human and robot.

It doesn’t help to just ignore humans either so that the robot would not need to participate in social interaction according to Lu:

“One area of efficient navigation is taking humans into consideration while navigating. It is socially suboptimal to ignore humans and merely think of them the same as static, inorganic obstacles. This leads to the person coming across with a robot hesitating on the robot’s actions, potentially resulting in a collision.”

The robot should instead try to fake it self to look act like a human for better results:

“…if the robot modifies its behavior to use a predictive model for the person, in which the person’s social behavior is taken into account, the person will recognize the social behavior and be able to create a theory-of-mind for the robot that is more similar to people.”

The “theory-of-mind” that David is referring to is the way we humans think that other people, animals or living things think. Based on our own experiences and how we think, we create a theory of how others think, which is often affected by their likes and dislikes, social behaviour and what they have done in their past. This is only your theory, since humans have such complex minds that you are merely trying to simplify it to something you can comprehend and predict. For example, if you come across to someone in the street you expect them to aligning to the right side of the sidewalk unless they are staring at their phone.

Now, I’ll go into what ideas came to me when I was reading the thesis.

Humans do a lot of their actions to achieve comfort. Internal things might annoy you (itching, pain, tickling) or external (noise, light, actions of others). I guess that getting annoyed is a light form of self-defence mechanism, which stems from survival instincts. You automatically try to avoid pain and loud noises in order to stay healthy and live longer. Now, robots do not have this. They might be programmed to avoid actions that lead to harm of themselves or harm of humans but what makes the difference is the severity of harm. I’m quite certain that any kind of scratch caused to a human is unacceptable but if the robot dents itself or kicks it’s toe to a furniture corner, it is probably not something that it avoids to do in the future. My estimate is that robots would be more relatable if they would have this heightened state of self protection, almost as if they would get annoyed if there is a possibility that they would get mildly hurt. We humans do that all the time – we try to predict and then avoid situations where we could be annoyed or lightly hurt.